Background and Methodology

As the number of human-made objects in orbit continues to grow, so does the risk from space debris. This includes everything from flecks of paint and lost astronaut tools to large satellites and rocket parts. The buildup of space debris, particularly in low earth orbit, poses real threats to active satellites, crewed missions, and the long-term use of space. Yet the full scope of the problem remains difficult to grasp. Key questions about the location, quantity, and origin of debris are often unclear or overlooked outside technical communities. This data snapshot aims to improve awareness of space debris and its origins.

This analysis maps the current distribution of debris across four key orbital regions: low earth orbit (LEO), medium earth orbit (MEO), geostationary orbit (GEO), and highly elliptical orbit (HEO). Each orbital region presents different opportunities, challenges, and use cases. For example, LEO hosts not only a wide array of communications and Earth observation satellites but also human space missions, whereas GEO is often used for stationary satellites, such as GPS. In this respect, the nature, risks, lifetimes, and country-level patterns of debris objects in each orbit vary, all of which are essential to understanding both the scale of the problem and who is responsible for it.

The data was sourced from the SPACE-TRACK.ORG Satellite Catalog, a U.S. Space Force-maintained and updated website that tracks and makes publicly accessible data on “more than 47,000 man-made objects” in space. The dataset includes all cataloged debris over 10 cm from 1958 through mid-April 2025.

This analysis is entirely descriptive and exploratory. Its goal is not to model the future or propose solutions, but rather to make visible what is often left opaque: where space debris lives, how long it persists, and who or what contributed to its creation.

The following charts show how individual events have reshaped the debris landscape. They identify and describe the largest sources of debris in orbit, highlight which countries and platforms have contributed the most, and show how a small number of events, particularly anti-satellite (ASAT) tests and satellite collisions, are responsible for much of the congestion in Earth’s orbital environment. Whether measured by active fragments, total debris ever created, or concentration in low earth orbit, the influence of ASAT testing is visible throughout the data that follows.

What Is Space Debris?

Over the past seven decades of human space activity, thousands of satellites, scientific instruments, crewed spacecraft, and other payloads have been launched into orbit. Alongside these missions, debris has steadily accumulated as a byproduct of normal operations. Spent rocket stages, defunct satellites, accidental breakups, and collisions all contribute to an orbital environment where debris can remain for years or decades before atmospheric drag slows it down sufficiently to reenter the Earth’s atmosphere and burn up (see Figure 1). Reentry occurs without human intervention in most cases, but its timing is difficult to predict and depends on altitude, mass (and area), and solar activity.

The result is a crowded orbital domain, particularly in low earth orbit (LEO). Here, active satellites for communications, navigation, intelligence, and research operate side-by-side with debris, ranging from tiny paint flecks to large inert spacecraft. At its peak in 2006, LEO was crowded with nearly 16,000 tracked pieces of debris, making it the most congested orbit and posing operational challenges for space actors. This should be unsurprising, as being the region closest to the surface of the Earth, our familiarity and knowledge of the orbit is greater. The majority of space activity takes place in LEO, and we have better visibility into its contours and contents. That same year, a Science article warned, “The current debris population in the LEO region has reached the point where the environment is unstable and collisions will become the most dominant debris-generating mechanism in the future.” Two decades later, this projection is proving increasingly correct—other than two outsized debris clouds generated by ASAT tests (one by China in 2007, and another by Russia in 2021), the LEO region still contains the overwhelming majority of debris—just over 83 percent of tracked objects, as of April 2025.

While Figure 1 shows a recent dip in catalogued debris, the long-term trend since 2000 is upward, driven by increased space activity. Temporary declines usually reflect solar activity, which expands the upper atmosphere and accelerates orbital decay, particularly at lower altitudes. But vast numbers of smaller, untracked fragments continue to threaten spacecraft, and long-lived debris persists in higher LEO orbits. At the same time, mitigation guidance has improved: international standards, national regulations, and measures such as the U.S. Federal Communications Commission’s five-year deorbit rule is encouraging operators to adopt more responsible end-of-mission disposal practices. Still, compliance is uneven, and without active debris removal, the overall environment remains unstable.

Even small fragments in LEO pose serious risks. A 10-centimeter object traveling at orbital velocity carries the destructive energy of several kilograms of TNT—comparable to a 550-pound object moving at highway speed on Earth. NASA has warned that orbital debris is the single greatest threat to satellites, spacecraft, and astronauts. The danger is not hypothetical: in 2016, a particle likely no larger than a paint fleck chipped the window of the International Space Station’s cupola, a reminder that even the smallest pieces of debris, most untracked, can compromise safety in orbit. The continued presence of long-lived debris in LEO increases the risk of collisions, complicates satellite operations, and raises the cost of maintaining safe and predictable access to orbit.

Who Contributes to Space Debris?

Framed in the 1967 Space Treaty as the “province of all mankind,” outer space is often imagined as a global commons. However, in reality, it is both technically challenging to access and governed by few enforceable rules. Governments largely set their own practices, and although commercial operators must obtain licenses for launches, spectrum, and orbital slots, oversight remains fragmented and inconsistent. This has resulted in uneven and often secondary debris mitigation measures, often overshadowed by commercial or national security priorities.

The scatter plot illustrates this concentration, with each point representing a unique debris object by name, launch date, and country of origins. Larger circles reflect events that produced larger clusters of fragments, sometimes known as “debris clouds.”

As Figure 3 below shows, the United States, Russia (and the former Soviet Union), and China are responsible for nearly 95 percent of catalogued debris currently in orbit. Other spacefaring states, including France, Japan, India, and the European Space Agency (ESA), have also produced debris, but their contributions remain comparatively small.

From Launch to Litter: How Does Space Debris Form—and Where Does It End Up?

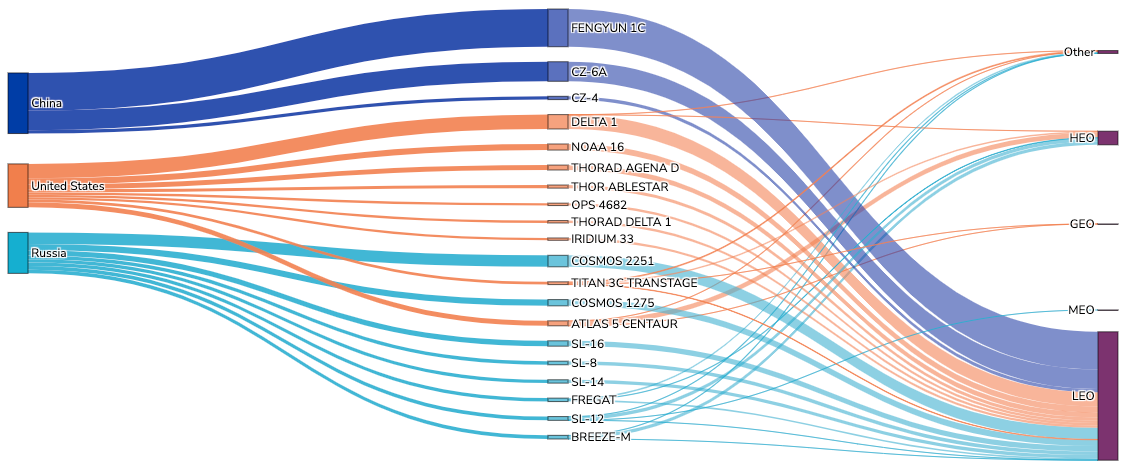

The charts in Figure 4 make clear that a small number of catastrophic events and abandoned single-use space launch vehicles are responsible for a vast majority of all active debris in orbit today. To be more precise, 73 percent of all pieces of tracked debris in orbit today can be attributed to just 20 major sources (each one described below in Table 1). A mixture of Russian rocket stages that fragmented after fuel explosions, U.S. payloads that broke apart after malfunctions, China’s 2007 ASAT test, and the 2009 Iridium–Cosmos collision, these 20 sources demonstrate how just a handful of high-impact events define the debris environment. These outliers underscore the urgent need to prevent future large-scale breakups, particularly in LEO, where satellite density is highest. Spent stages and broken-up satellites pose major issues in space, but space operators, states, and private companies can take significant steps to prevent such incidents. Compared to LEO, the orbits of MEO, GEO, and HEO (which host fewer satellites) have seen fewer catastrophic events.

Table 1: Top 20 Sources of Space Debris

The single largest contributor of currently active debris is China’s 2007 ASAT test against the Fengyun-1C weather satellite, which created more than 3,400 fragments at the time of the event. Of those, nearly 2,500 remain active today, representing almost 19 percent of all tracked debris still in orbit. ASAT tests have been problematic for the creation of space debris, but the FY-1C test represents an outsized impact on the creation of debris.

ASAT weapons are systems designed to disable or destroy satellites in orbit, often by striking them directly at high speed. These tests create massive debris clouds, making them one of the most destructive single sources of long-lasting orbital debris. Russia’s 2021 strike on Cosmos-1408 had a similarly dramatic effect, as the second-largest single debris-causing event of all time (after the FY-1C test), with debris comprising over 10 percent of the total debris in orbit in that year (by 2024, the debris had largely since decayed).

A handful of upper-stage fragmentations dominate today’s debris environment. The United States’ Delta 1 and Atlas 5 Centaur, China’s CZ-6A, and Russia’s SL-16 rocket stages—left in orbit after successful missions—form some of the largest debris clusters, reflecting an era before deorbiting became a common practice.

While most debris from these “top 20 sources” is in LEO, there are some fragments that exist in higher orbits. HEO hosts a smaller but noteworthy share, much of it from Soviet-era missions intended for communications and surveillance over high latitudes.

MEO, which supports navigation systems such as GPS, Galileo, GLONASS, and BeiDou, has comparatively little debris but is especially important given its critical role in global positioning and timing. GEO, the orbit of choice for communications, weather, and intelligence satellites, benefits from stronger international norms on disposal. At the end of their lives, most GEO satellites are moved into designated graveyard orbits to limit long-term accumulation.

The “Other” category encompasses debris in transitional or nonstandard trajectories, often resulting from transfer stages, failed maneuvers, or disposal attempts that do not neatly fit into LEO, MEO, GEO, or HEO.

How Is Space Debris Removed from Orbit?

Objects that are no longer active often remain in orbit for years, sometimes decades, because of the difficulty and expense of removing them. Historically, there were limited plans for deorbiting missions at end of life until standards began to emerge that emphasized the importance of disposal. Although advances in launch technology have made access to orbit somewhat easier, space operations remain complex and costly. This reality underscores the cumulative nature of the debris problem known as the Kessler Syndrome. Once created, debris persists until it is deliberately removed or gradually pulled down by atmospheric drag. There might be a point where the space debris in Earth’s orbit (and LEO in particular) becomes so dense that collision events between objects trigger a cascading chain reaction, creating exponentially more debris.

In LEO, the average lifetime of a fragment is more than 15 years (about 5,600 days) before drag causes reentry. In higher orbits, such as HEO or other atypical trajectories, debris can last for hundreds of years because atmospheric effects are negligible. GEO and MEO show somewhat shorter average debris lifetimes, not because of natural decay but because of more systematic disposal practices. Satellites in GEO are usually maneuvered into “graveyard orbits” at the end of service, while navigation satellites in MEO are sometimes lowered into disposal orbits to accelerate orbital decay. The message is clear: debris is not a temporary issue but a long-term legacy of every launch.

To reduce this buildup, governments and private actors are developing active debris removal technologies. Concepts under study include robotic arms, nets, harpoons, tethers, and drag-enhancing devices. Companies such as Astroscale (based in Japan and the United Kingdom) and ClearSpace (based in Switzerland, under contract with the ESA), along with U.S. and European startups, are testing debris-removal demonstrations. Yet these projects face steep costs, technical challenges, and legal uncertainties over responsibility and liability. Moreover, debris removal technologies are inherently dual-use: the same systems that can deorbit a defunct satellite could also be employed to capture or disable an active one. This concern is heightened by China’s growing interest in debris removal, which U.S. analysts and military officials note could serve both civilian and defense purposes.

Conclusion

The real challenge ahead is not so much the entry of new players, but the rapid growth in planned satellite constellations by existing major actors. Companies such as SpaceX, OneWeb, and Amazon’s Kuiper, alongside large-scale Chinese constellations, will place tens of thousands of satellites into LEO in the coming decade. This will increase congestion, heighten the tracking burden for space surveillance networks, and multiply the need for collision avoidance measures. The more crowded orbit becomes, the greater the risk that even a single breakup event could have cascading effects.

The concentration of debris among a small number of states creates both risks and opportunities. China and Russia are unlikely to enter into binding international agreements on debris, and Beijing in particular may view debris removal tools as potential strategic assets. At the same time, the United States and its allies can lead by example by setting shared debris mitigation standards, expanding space situational awareness, and strengthening multilateral cooperation. While the Artemis Accords primarily address exploration and resource use beyond Earth, the coalition-building model they represent could also be applied to debris governance. With only a handful of actors responsible for the overwhelming share of orbital debris, there is a narrow but significant opportunity for coordinated international action.