U.S. export controls, as they stand, do not control the provision of cloud computing services, nor do they stop Chinese companies from accessing controlled chips via Cloud Service Providers (CSPs).

Goal 1, described in Part 1 of this series, is focused on controlling cloud computing services that provide a China-located user with access to an advanced chip controlled under the October 7 regulations. In this post, we will cover a second possible goal, highlight examples displaying how such controls might work, and discuss the advantages, disadvantages, and limitations of implementing controls in this manner.

Goal 2 is as follows:

Restrict U.S. CSPs from providing any cloud computing service in support of military, security, or intelligence services end uses and end users in China.

In Part 2, we identify situations where it appears current U.S. export controls can be used to restrict cloud computing services, as well as situations where they cannot. As controls stand now, we do not recommend applying broad technology controls on cloud computing services to all entities in China, because, based on our analysis, it does not appear feasible and may have adverse consequences. However, there may be more targeted and feasible policy solutions that focus on specific problematic actors in China. Forthcoming research from the Center for Security and Emerging Technology (CSET) and the Center for a New American Security (CNAS) will provide a more detailed analysis of this issue, outline additional recommendations, and consider policy options, such as making Infrastructure-as-a-Service (IaaS) directly controllable under the Export Administration Regulations (EAR) and implementing “Know Your Customer” rules for CSPs.

Understanding U.S. Policy: How Export Controls Do and Do Not Cover Cloud Computing

As we discussed in Part 1, the Bureau of Industry and Security (BIS) at the Department of Commerce has taken the position that providing cloud computing services is not subject to the EAR. Moreover, BIS treats the user/customer of a cloud computing service—not the CSP—as the “exporter” in question. For these reasons, the EAR’s item-based controls, end use controls, and end user controls—each of which applies only to physical goods, software, and technology—do not control cloud computing services. This, we argue, leaves one remaining option under the EAR: controls on the activities of “U.S. persons.”

These controls allow the U.S. government to restrict “U.S. persons”—including U.S. citizens (wherever they are located around the world), permanent residents, U.S. companies, and any person located in the United States—from engaging in activities that “support” certain restricted activities. “Support,” in the context of “U.S. persons” controls, hinges on the “U.S. persons” having knowledge that their activities or services are in support of a controlled end use or for a controlled end user. Already highly complex as they stand, these controls are even more complicated in the context of controlling cloud computing services, which we will discuss in more detail below.

As argued in Part 1, “U.S. persons” being involved in the sale of cloud computing services is the only legal hook under the EAR that the U.S. government could use to achieve Goal 1: control the provision of advanced cloud computing services to any end user in China. BIS arguably has the statutory authority to expand controls to do this, but this authority has yet to be implemented in the EAR.

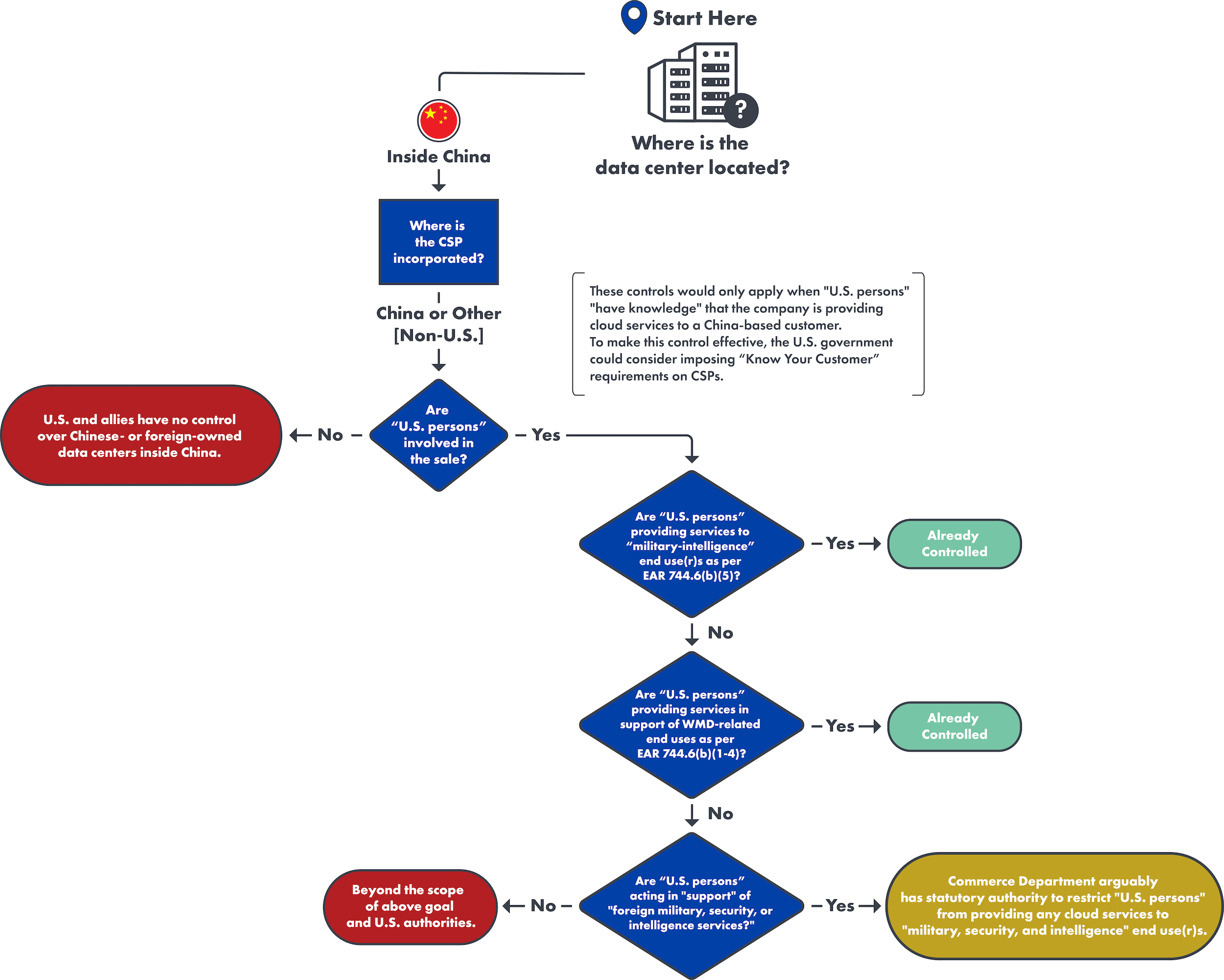

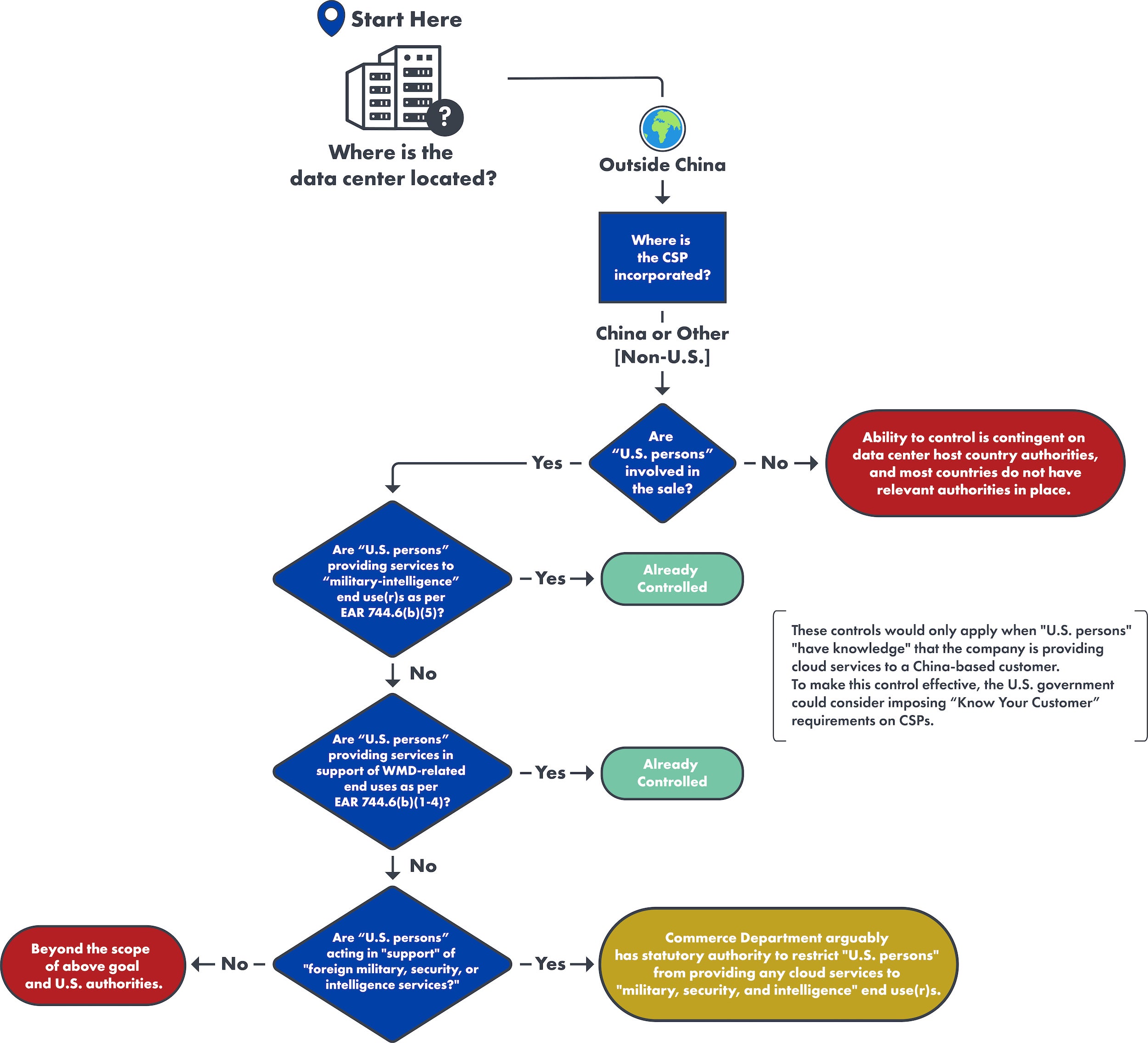

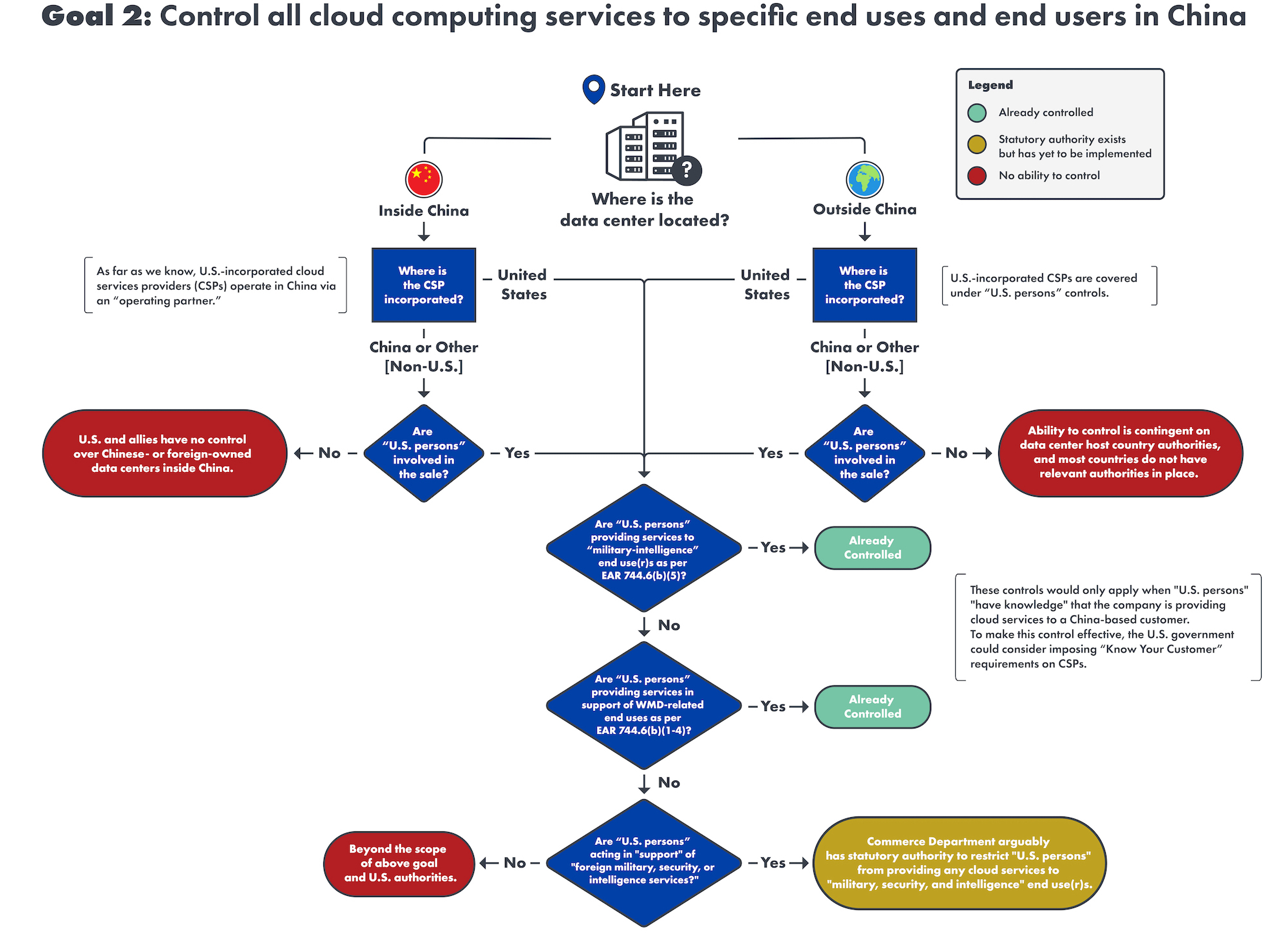

The flowcharts below demonstrate how “U.S. persons” involved in the sale of cloud computing services can also be used as the legal hook for the U.S. government to achieve Goal 2.

Goal 2: Restrict U.S. CSPs from providing any cloud computing service in support of military, security, or intelligence services end uses and end users in China.

Goal 2 aims to prevent actors that are part of or closely connected to foreign military, intelligence, or security activities in a country of concern, including (but not limited to) China, from using U.S. CSPs’ services. It also seeks to prevent U.S. CSPs’ services more broadly from being used for military, intelligence, and security purposes.

An export control created to achieve this goal could apply to both advanced (chips that exceed the October 7 performance thresholds) and less advanced cloud computing services. Goal 2 assumes that the provision of any cloud computing service by a U.S. CSP to a problematic Chinese actor is not in the national security or foreign policy interests of the United States. This would include, for instance, the provision of cloud computing services to the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) or to Chinese companies complicit in ongoing surveillance of the Uyghur population in Xinjiang.

Since January 2021, the EAR prohibits “U.S. persons” (wherever located) from supporting “military-intelligence” end uses or “military-intelligence” end users, as well as end uses related to the proliferation of weapons of mass destruction (WMDs). It is important to note that “military-intelligence” in this context only covers a very narrow set of activities—those that support the intelligence arms of foreign militaries (including but not limited to the Intelligence Bureau of the Joint Staff Department of the PLA).1

In December 2022, Congress broadened BIS’s authority to regulate the activities of “U.S. persons,” regardless of location, when found to be in “support” of “foreign military, security, or intelligence services.” This one-sentence change now provides BIS with the clear statutory authority to create and impose controls on these three types of activities, even when the underlying items in context are not subject to the EAR. This statutory authority, however, has not been implemented in the EAR as of the time of writing.2

We argue that these existing “U.S. persons” controls, in conjunction with new authorities, could be used to restrict U.S. CSPs from providing cloud computing services to or in support of China’s military, security, and intelligence activities.

Let’s consider a few examples of how U.S. regulations could be shaped to achieve this goal for hypothetical CSPs in different jurisdictions. We will refer to hypothetical CSPs based on their country of incorporation (e.g., “Chinese CSP-owned data center” refers to a data center owned by a China-incorporated CSP).

Data Centers inside China

Example: Chinese CSP-owned data center in China

Walking through the flowchart:

- A Chinese CSP-owned data center—for instance, a Baidu Cloud data center located in Beijing—is not itself a “U.S. person.” As such, BIS’s ability to restrict the CSP from offering cloud computing services to an entity in China is dependent on whether the CSP in question employs “U.S. persons” who are involved in the sale.

- If no “U.S. persons” are involved in the sale of the cloud computing service, then the United States has no control over a Chinese CSP-owned data center in China. Since no other country has the equivalent of “U.S. persons” controls, U.S. allies do not have the ability to control these activities either, even if their citizens were involved in the sale.

- If “U.S. persons” are involved in the sale of the cloud computing service…

- …and these “U.S. persons” are providing cloud computing services to “military-intelligence” end use(r)s and/or in support of WMD-related end uses, BIS already has existing regulations in the EAR to control all support (including cloud computing services) offered to these specific end use(r)s.3

- …and these “U.S. persons” are acting in support of “foreign military, security, or intelligence services,” BIS has the statutory authority to restrict “U.S. persons” from offering access to cloud computing services to these end users and for these end uses in China. However, this authority has not yet been implemented in the EAR.

- If “U.S. persons” are involved but are not acting in support of or providing cloud computing services as described by either of the two sub-bullets above, controlling those services is beyond the scope of our named objective (controlling all cloud computing services to problematic end use(r)s in China) and U.S. authorities.

Data Centers outside China

Example: French CSP-owned data center in Indonesia

Walking through the flowchart:

- A French CSP-owned data center—for instance, OVHcloud—is operated by a French-incorporated company and is therefore not itself a “U.S. person.” As such, the U.S. government’s ability to restrict the CSP from offering cloud computing services to an entity in China is dependent on whether the CSP employs “U.S. persons” who are involved in the sale of these services. It may also depend on the regulatory authorities of the country in which the data center is located.

- If no “U.S. persons” are involved in the sale of the cloud computing service, then the United States has no control over a French CSP-owned data center in Indonesia, for example. Since no other country has the equivalent of “U.S. persons” controls, U.S. allies do not have the ability to control these activities either, even if their citizens were involved in the sale.

- If “U.S. persons” are involved in the sale of the cloud computing service…

- …and these “U.S. persons” are providing cloud computing services to “military-intelligence” end use(r)s and/or in support of WMD-related end uses, BIS already has existing regulations in the EAR to control all support (including cloud computing services) offered to these specific end use(r)s.4

- …and these “U.S persons” are acting in support of “foreign military, security, or intelligence services,” BIS has the statutory authority to restrict “U.S. persons” from offering access to cloud computing services to these end users and for these end uses in China. However, this authority would first have to be implemented in the EAR.

- If “U.S. persons” are involved but are not acting in support of or providing cloud computing services as described by either of the two sub-bullets above, controlling those services is beyond the scope of our named objective (controlling all cloud computing services to problematic end use(r)s in China) and U.S. authorities.

Limitations and Conclusion for Goal 2

Attempting to achieve Goal 2 presents complexities and limitations similar to those of Goal 1. First, as mentioned in the previous post, attempts to coordinate these controls with like-minded countries would be difficult, and U.S. companies would disproportionately bear the costs associated with compliance. In the instance of Goal 2, entities that the U.S. government may deem to be complicit in foreign military, security, or intelligence activities may be viewed differently in other countries, and without a shared definition, interpretations—and subsequent policy choices—could vary significantly. Without any plurilateral agreement, the United States is only able to restrict access to cloud computing services when “U.S. persons” are involved in the sale of the service. This could incentivize foreign CSPs to remove “U.S. persons” from their sales and support teams in order to avoid U.S. licensing requirements. To the extent that foreign CSPs are successful in this effort, it may also put U.S. CSPs at an economic disadvantage relative to their foreign competitors, as they themselves cannot avoid “U.S. persons” controls.

Second, to make “U.S. persons” controls effective in the pursuit of this objective—controlling all cloud computing services to problematic end use(r)s in China—the U.S. government would need to place new due diligence requirements on U.S. CSPs, which we will consider in an upcoming report. As explained in the EAR, individuals and firms must satisfy due diligence requirements when exporting items subject to the EAR. Since services—including cloud computing services—are not subject to the EAR, CSPs are exempt from these requirements. Therefore, as U.S. policy stands now, CSPs are not required to collect information on their customers’ location or identity—information that would be needed to control the activities of “U.S. persons” as specified in the above goal. For example, even if BIS implemented a “U.S. persons” control on cloud computing services sold to problematic Chinese actors tomorrow, providers would only be liable if BIS discovered after the fact that the CSP had knowledge of providing a controlled cloud computing service into China. Until this changes—perhaps through new “Know Your Customer” requirements—controls on cloud computing services will likely be ineffective. Future work from CSET and CNAS will go deeper on this issue.

Lastly, even with the implementation of new controls on “U.S. persons” and complementary “Know Your Customer” requirements, the process of identifying problematic actors in China has and will continue to be a challenge for U.S. companies and BIS enforcement. It is nearly impossible to confidently assert that any Chinese entity is a provably commercial actor, thanks in part to China’s military-civil fusion strategy. This is not to say that the U.S. government should not attempt to identify problematic actors in China; rather, it means that U.S. government and U.S. companies must enter into business transactions with Chinese entities with eyes wide open and assume that some amount of risk will always exist when working in China.

See the full flowchart—combining data centers located inside and outside China—for Goal 2 below:

Notes

- China in this context includes both Hong Kong and Macau.

- As of June 2023, it is difficult to determine how China’s cross-border data flow regulations will be implemented. We assume that the regulations will incentivize Chinese entities to access cloud computing services via domestic Chinese data centers.

- Foreign subsidiaries of U.S. CSPs are not directly subject to “U.S. persons” controls because “U.S. persons” as defined by the EAR does not include separately established foreign subsidiaries of U.S. firms. However, the activities of “U.S. person” employees, managers, and directors of the subsidiary would be subject to EAR 744.6. This also applies to U.S. CSPs operating outside of China.

- As explained in Supplement No. 3 to Part 732 of the EAR, individuals and firms must satisfy due diligence requirements when exporting items subject to the EAR. Since services—including cloud computing—are not subject to the EAR, they are exempt from these requirements. As a result, CSPs are not required to collect information on their customers’ identity or location—knowledge that would be needed to control the activities of U.S. persons as specified in Goal 2. Until this changes, controls on cloud computing services are likely to be ineffective.

- https://www.ecfr.gov/current/title-15/subtitle-B/chapter-VII/subchapter-C/part-744/section-744.22#p-744.22(f)(2)(iv)

- “James M. Inhofe National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2023,” https://www.congress.gov/bill/117th-congress/house-bill/7776/text?s=3&r=1&q=%7B%22search%22%3A%5B%22hr7776%22%2C%22hr7776%22%5D%7D; Kevin J. Wolf, et. al, “BIS Has New Authorities to Impose Controls over Activities of US Persons in Support of Foreign Military, Security, or Intelligence Services.” https://www.akingump.com/en/insights/alerts/bis-has-new-authorities-to-impose-controls-over-activities-of-us-persons-in-support-of-foreign-military-security-or-intelligence-services

- Imagine a “U.S. person” employed by Baidu Cloud in Beijing who “has knowledge” that they are providing cloud computing services to—for example, the Intelligence Bureau of the Joint Staff Department of the PLA. That activity would require a license under the “military-intelligence” end users provision of the EAR.

- Imagine a “U.S. person” employed by OVHcloud (a French CSP) who “has knowledge” that they are providing cloud computing services in support of—for example, “the design, ‘development,’ ‘production,’ operation, installation (including on-site installation), maintenance (checking), repair, overhaul, or refurbishing of nuclear explosive devices” in China. That activity would require a license under the WMD-related end use provision of the EAR.