Executive Summary

The United States and its allies enjoy a competitive advantage in the production of artificial intelligence chips necessary for leading AI research and implementation.1 CSET has identified photolithography equipment as a key constraint in China’s ability to manufacture leading edge chips with feature sizes of 45 nanometers and below.2 Essential photolithography equipment is sold only by companies in the Netherlands and Japan, with related research and development in the United States. Coordinated export controls applied by these three countries on photolithography equipment— most importantly, steppers—could preserve U.S. and allied technological advantages and make China dependent for the near- to mid-range on imports of U.S. and allied chips for high-end AI applications.

Key findings include:

- AI chips—highly specialized integrated circuits—are critical to quickly and efficiently train or deploy advanced AI algorithms.

- AI chip supply chains, especially the most high-value components, are highly globalized and concentrated in a small number of companies in a small number of countries.

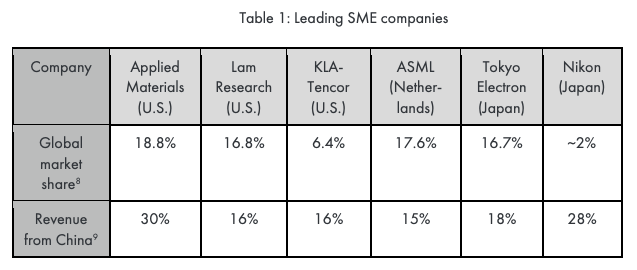

- Photolithography equipment, which is dominated by Dutch and Japanese companies, is the primary choke-point in China’s AI chip supply chain, while deposition, etching, and process control equipment, dominated by U.S. and Japanese companies, are secondary choke-points.

- China very likely will fail to build a competitive photolithography industry within the next decade due to its skilled labor shortfall, the technical complexity of the technology, and the monopolistic advantages of incumbents.

Maintaining the AI Chip Competitive Advantage of the United States and its Allies

Download Full Issue Brief- In this paper, AI refers to modern compute-intensive AI techniques, particularly deep learning.

- AI chips represent an archetypal technology following the logic of strategic dependency where “a concentration of foreign suppliers impose a negative externality for the importing state, represented by the potential economic and security costs of being cut off from accessing these items,” where such assets have “low price elasticity” of both supply and demand, and “broad, ongoing flows.” Allan Dafoe and Jeffrey Ding, “The Logic(s) of Strategic Assets” (forthcoming). Another model terms this dynamic “weaponized interdependence,” where a state with political authority over central nodes of international networks designed to generate market efficiencies is deployed to choke off adversaries from economic and information flows. Henry Farrell and Abraham L. Newman, “Weaponized Interdependence: How Global Economic Networks Shape State Coercion”, International Security, Vol. 44, No. 1 (Summer 2019): 42-79, https://www.mitpressjournals.org/doi/full/10.1162/isec_a_00351.