Over the past year, critics of the Biden administration’s approach to China have pointed to the U.S. Department of Commerce’s Entity List, stating that the Bureau of Industry and Security’s (BIS) export control licensing process fails to protect critical technologies from being traded to key adversaries. Publicly available data from BIS play an important role in these policy discussions. Following our last data snapshot, here we provide additional guidance on how to interpret data published by BIS to make more accurate assessments on the policy direction of export controls on China. This data snapshot is designed to help the policy community understand how best to approach policy issues that are heavily reliant on interpreting data and does not attempt to judge the effectiveness of BIS or speak either in favor or against BIS licensing policies.

What is BIS Data?

BIS releases annual statistical reports covering the state of trade with key partners, including China, over the previous fiscal years. These annual reports include statistics on the export licensing process along with information regarding general trade trends. There are several important things to keep in mind when assessing this data, especially when looking at trends over time or across presidential administrations. Previously, we covered that:

- Accounting for the types of items subject to the authority of the BIS and their sensitivity levels is critical for thorough analysis. Aggregated BIS data does not allow insight into the share of highly sensitive items.

- The broader context of BIS data impacts conclusions. Comparing calculated statistics across time periods and to other relevant datasets changes the conclusions.

- Excluding available data can skew the approval rate. Including licenses returned without action lowers China’s license acceptance rate by 20 percentage points.

Additional Things to Keep In Mind When Using BIS Data

1. The monetary value of reviewed licenses matters and provides additional insight into license size and impact.

Each license reviewed by BIS has different export values. Strictly looking at approval versus denial rates ignores the impact of the license size. Table 1 shows that the total export value of denied applications has increased dramatically since FY 2020. This increase in the value of denied licenses happened despite a small decrease in the approval rate for applications since FY2020 (see our last data snapshot).

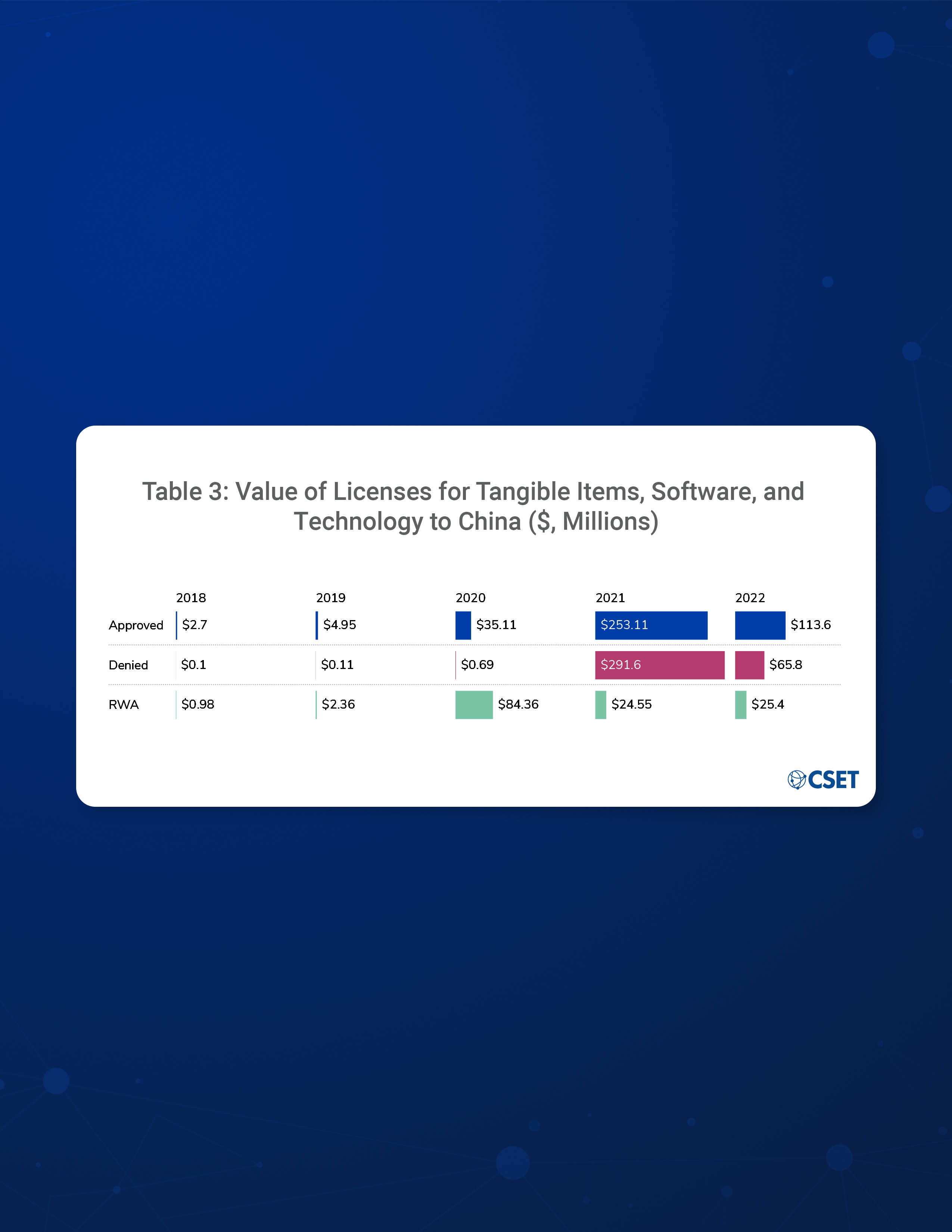

Table 1: Value of Licenses for Tangible Items, Software, and Technology to China ($, Millions)

Source: BIS, U.S. Department of Commerce.

Note: Values include Hong Kong.

This rise in the value of denied license applications shows that the value of reviewed licenses provides important additional information, along with the number of denied licenses. BIS denial of seemingly few licenses nonetheless impacts the trading relationship between the United States and China as it pertains to critical software and technologies. The first year of the Biden administration recorded the highest value of denied licenses to China in this five-year period, with $291.6 million denied in FY 2021 compared to just $0.69 million in FY 2020. Moreover, Table 1 shows that in FY 2021, the Biden administration denied a higher dollar amount in export licenses than it approved, suggesting that the administration may have been approving more, smaller licenses while denying fewer, larger licenses. The inclusion of license value critically impacts relevant policy discussions, as it allows additional insight into the size and impact of the licensing process.

2. Reporting from BIS may appear inconsistent due to changes across different administrations and policies toward specific countries.

Different presidential administrations have different national security objectives and, as such, may use export controls in different ways. This has certainly been the case since both the Trump and Biden administrations have chosen to use export controls in unique ways beyond their traditional nonproliferation objectives. Because of this variance, analysts and policymakers should be careful when comparing one year of one administration to another without this broader context.

There are substantial differences in terms of how the Trump and Biden administrations pursued their export control licensing policies. As Table 1 shows, the Trump administration handled significantly smaller export control license applications, averaging $14 million in approvals and $0.3 million in denials from 2018 to 2020. In one less year of data, the Biden administration approved an average of $183 million and denied an average of $178.7 million from 2021 to 2022. The Biden administration’s increase in export control activity also results in a greater parity—either by percent or value difference—between the values of approved and denied licenses relative to the Trump administration.

In addition to export control and licensing-specific policies, broader policy changes across an administration can and have impacted export control data collection and reporting. For instance, in 2020, the Trump administration made the decision to no longer treat Hong Kong as an autonomous region separate from China and ordered relevant agencies to align Hong Kong-specific policies under broader U.S. policies toward China. This led to the removal of Hong Kong as a separate export destination from China under the Export Administration Regulations (EAR), and as a result, BIS began consolidating Hong Kong’s export licensing numbers with China’s in 2021.

Table 2: Comparison of Average China Licensing Data with and without Hong Kong, 2018-2021

Source: BIS, U.S. Department of Commerce.

Note: BIS did not incorporate Hong Kong numbers into its China values until 2022.

For the purposes of this data snapshot, Hong Kong’s export statistics are retroactively aggregated with China’s to reflect the current status of U.S. policy. Failure to do so results in a 6% average difference in the presented totals (as demonstrated by Table 2). Although relatively small in this instance, failing to contextualize these numbers within broader policy maneuvers may result in misunderstanding.

Conclusion

Publicly available data on U.S. policy tools is critical to maintaining an informed and active policy base. The information provided by BIS and other federal agencies allows the general public and relevant policymakers to conduct analysis and draw conclusions about the efficacy of policy tools like export controls. Based on our assessment in this latest Data Snapshot series, we outline some best practices for leveraging publicly available export control data in trade policy analysis and commentary:

- Accounting for the types of items subject to the authority of the BIS and their sensitivity levels is critical for thorough analysis. Aggregated BIS data does not allow insight into the share of highly sensitive items.

- The broader context of BIS data impacts conclusions. Comparing calculated statistics across time periods and to other relevant datasets changes the conclusions.

- Excluding available data can skew the approval rate. Including licenses returned without action lowers China’s license acceptance rate by 20 percentage points.

- The monetary value of reviewed licenses matters and provides additional insight into license size and impact. Analyzing license value, in addition to approval ratings, impacts conclusions.

- Reporting from BIS may appear inconsistent due to changes across different administrations and in broader U.S. government policies towards specific countries. Export controls are one of many policy levers available to administrations, and the publicly available data will reflect each administration’s priorities.