Over the past year, critics of the Biden administration’s approach to China have pointed to the U.S. Department of Commerce’s Entity List, stating that the Bureau of Industry and Security’s (BIS) export control licensing process fails to protect critical technologies from being traded to key adversaries. Statistics using publicly available BIS data, like the share of licensing approvals, often play a role in these policy discussions. For example, House Foreign Affairs Committee Chairman Michael McCaul said “it is absolutely astounding BIS approved more than $23 billion worth of licenses to sell U.S. technology to blacklisted companies based in China,” claiming that only 8% of licenses to these Entity Listed companies were denied. In August 2022, The Wall Street Journal reported that the “Commerce Department-led process that reviews U.S. tech exports to China approves almost all requests and has overseen an increase in sales of some particularly important technologies, according to an analysis of trade data.” However, these critiques are examples of neglecting to report the full picture of BIS data.

The purpose of this data snapshot is to provide guidance on how to interpret data published by BIS to make more accurate assessments on the policy direction of export controls vis-à-vis China. Beyond BIS and export controls in particular, this data snapshot aims to help the policy community understand how best to approach policy issues that are heavily reliant on interpreting data. This data snapshot does not attempt to judge the effectiveness of BIS or speak either in favor or against BIS licensing policies.

What is in BIS Data?

BIS releases annual statistical reports covering the state of trade with key partners, including China, over the previous fiscal years. These annual reports include statistics on the export licensing process, along with information regarding general trade trends. The reports cover both categories of export items subject to BIS authority, the first being those on the Commerce Control List (CCL). BIS maintains the CCL, which includes commodities, software, and technology that are subject to their export control authority. Items on the CCL include one of 14 reasons for control, which impacts their sensitivity levels. For example, items bearing the National Security (NS) reason for control have been determined to make a significant contribution to the military potential of any country/countries that would prove detrimental to U.S. national security. The second category of items includes either those not identified on the CCL or those not requiring a license for export due to being widely available, difficult to control, or minimally impactful, but which are still subject to BIS authority. For example, any items subject to the Export Administration Regulations (EAR) but not identified on the CCL are designated as EAR99 and still subject to BIS authority.

There are several important things to keep in mind when assessing this data, especially when looking at trends over time or across presidential administrations. A few of these considerations are identified below. For the purposes of this data snapshot, Hong Kong’s export statistics are retroactively aggregated with China’s to reflect the current status of U.S. policy.

Things to keep in mind when using BIS data

1. Accounting for the types of items subject to the authority of the BIS and their sensitivity levels is critical for thorough analysis.

Aggregate data provided by BIS does not account for the sensitivity levels of the controlled items. Many low-sensitivity items (e.g., EAR99) can be approved quickly and with no impact on U.S. national security, whereas licenses for highly sensitive items (e.g., NS-level items) are rarely approved. This means that aggregated approvals data is likely to include more low-sensitivity items. Extreme care must be taken when interpreting export license approvals and denials without also considering the sensitivity of the items being exported. Given license application data is not released at the sensitivity level, this point is especially important.

2. Looking at the broader context matters.

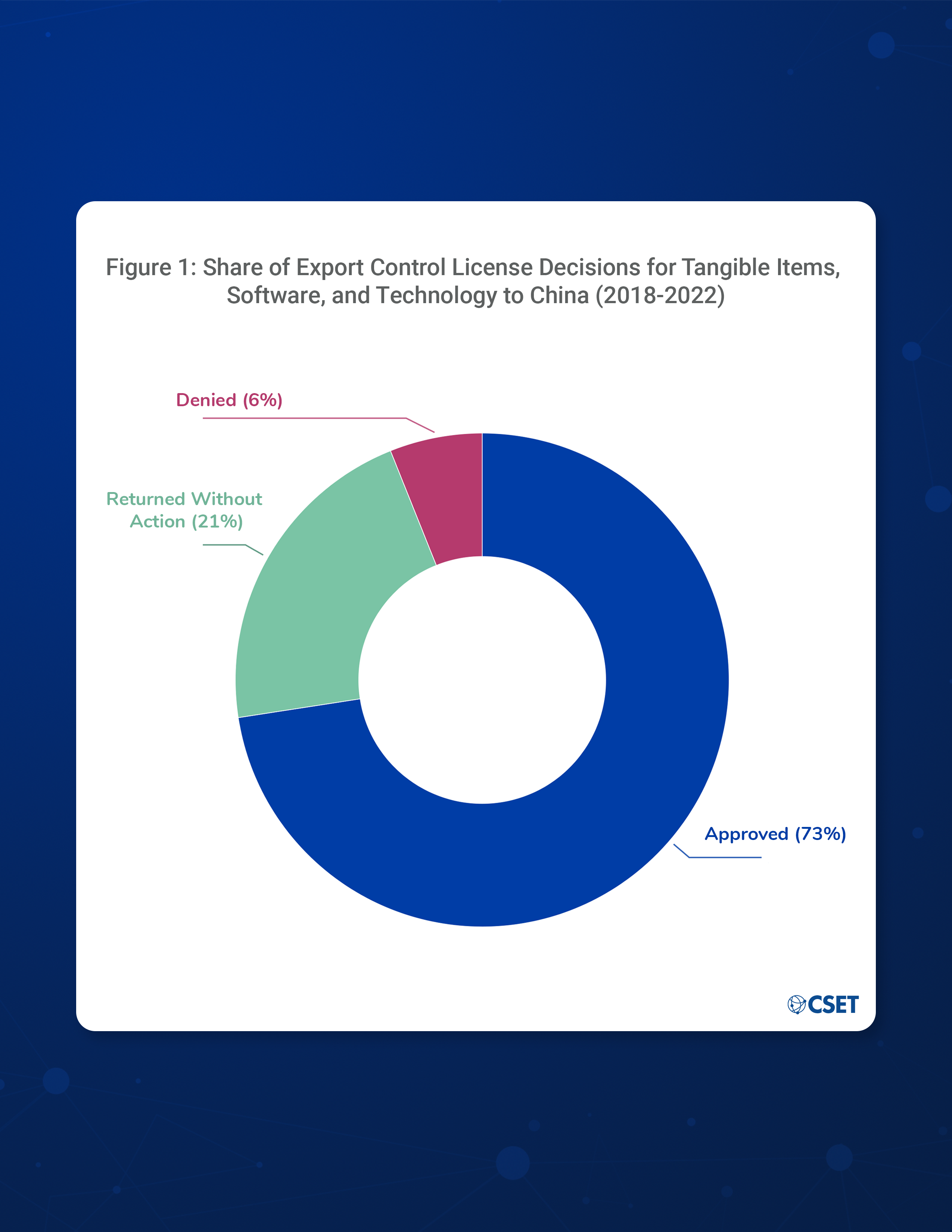

Applying for export licenses is an expensive and lengthy process. In FY 2022, the average processing time was 79 days, or roughly 2.5 months. Firms do not apply for an export license unless they expect it to be approved. If a firm expects a license to be denied, in the majority of cases, they will not go through the expenses and time to apply for a license in the first place. As demonstrated in Figure 1, the number of licenses approved is consistently higher than the number of licenses denied, when analyzing decisions for export licenses to China over the past five years.

Figure 1: Share of Export Control License Decisions for Tangible Items, Software, and Technology to China (2018-2022)

Source: BIS, U.S. Department of Commerce.

Note: The values in this table excludes deemed exports and all values include Hong Kong.

Note: BIS can return that license without a decision, denoted in BIS reporting as “Returned Without Action” or RWA.

This trend is also not unique to BIS; for instance, in FY 2021, the U.S. Department of State’s Directorate of Defense Trade Controls (DDTC)—the agency in charge of administering the International Traffic in Arms Regulations (ITAR)––denied only 0.7% and approved 81% of export control licenses. Given the high approval ratings from direct military-use items, it is not surprising to see similarly high approval rates for dual-use technologies covered by export control applications. Calculating statistics over longer periods of time and examining results from comparable datasets will impact the conclusions drawn from the BIS data.

3. Choosing to exclude available data can skew the approval rate.

In addition to being approved or denied, if the entity applying for a license does not provide BIS with sufficient information or provide information in a timely fashion, BIS can return that license without a decision, denoted in BIS reporting as “Returned Without Action” or RWA.1 In assessing trends across licensing data year over year, choosing to include (or not include) the RWA licenses impacts the reported approval rates.

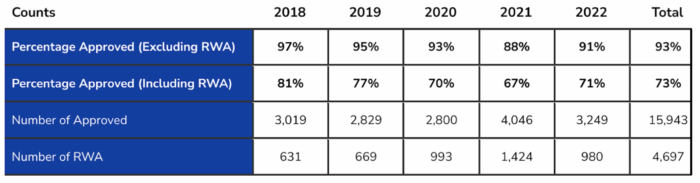

For tangible items, software, and technology exports, BIS reported reviewing “4,553 export/re-export license applications [in FY 2022] valued at $204.8 billion for China, compared to 39,045 applications worldwide valued at $335.9 billion.” In other words, almost 12% of all export/re-export license applications that year were for tangible items, software, and technology exports to China, accounting for almost 61% of the total value of all license applications reviewed that year. According to The Wall Street Journal, BIS “approves nearly all” of these license applications, but the inclusion of licenses returned without action alters the reported approval rates and discussions relating to export control policy. Table 1 shows the calculated acceptance rates for tangible items, software, and technology to China, excluding and including licenses returned without action (RWA).

Table 1: Percentage of Applications Approved, Including and Excluding RWA (FYs 2018-2022)

Source: BIS, U.S. Department of Commerce.

Note: The values in this table excludes deemed exports and all values include Hong Kong.

Without the RWA value, the average approval rate from 2018 to 2022 is 92%, which confirms the point of nearly all licenses being approved. However, when including the RWA value, the average approval rate decreases by 20 percentage points from 93% to 73%. This comparison of approval rates echoes the importance of proper data practices for researchers and policymakers alike. This 20 percentage point difference still means that the share of license approvals is higher than the share of denials during this entire period, but it more accurately captures BIS activity and serves as a reminder that all licensing data must be used in calculations and reported clearly.

Conclusion

Publicly available data on U.S. policy tools, including information provided by BIS and other federal agencies, allows the general public and policymakers to conduct analysis and draw conclusions about the efficacy of policy tools like export controls. To complement our assessment above, we conclude with some best practices for leveraging publicly available export control data in trade policy analysis and commentary:

- Publicly available data exists as a result of policies that may change over administrations and as a result of geopolitical events. A thorough understanding of the underlying policy framework and geopolitical trends is necessary for useful and accurate analysis.

- Assessments drawn from publicly available data can vary based on the data and methods utilized. A clearly reported methodology is needed for a complete analysis.

- The numerators and, more importantly, the denominators of calculated statistics influence the conclusions drawn. Proper reporting of calculations ensures transparency.

- Publicly available figures can be utilized to support a variety of claims. Check the original data sources to ensure all numbers are being reported accurately and honestly.

- Publicly reported data can be revised by the advising agencies. Periodic updates to any reported figures are required for accurate reporting.