On October 30, 2023, the Biden administration released the Executive Order on the Safe, Secure, and Trustworthy Development and Use of Artificial Intelligence (AI), which demonstrated the White House’s commitment to expanding the United States’ AI workforce and AI education ecosystems. Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics (STEM) graduates can aid the development of a highly skilled technical workforce, enabling technological innovation and economic growth. As tech competition intensifies globally, demand for STEM talent will continue to rise. Countries with more STEM graduates are better poised to make technological breakthroughs in fields like artificial intelligence, biotechnology, and advanced materials.

In this blog post, we analyze the current global distribution of STEM graduates using data from 2020, the most recent education statistics available across the countries included in this study. This analysis serves as an update to key figures originally published in the 2016 World Economic Forum Human Capital report.

Examining Total STEM Graduates by Country

Throughout most of the 20th century, the United States and Europe—particularly Russia, Germany, the UK, and France—were considered the global centers of scientific and technological education. In the last few decades, however, new players have emerged. In Asia, countries like China, India, South Korea, and Japan rapidly expanded their STEM education programs and today produce significant numbers of graduates in STEM fields.

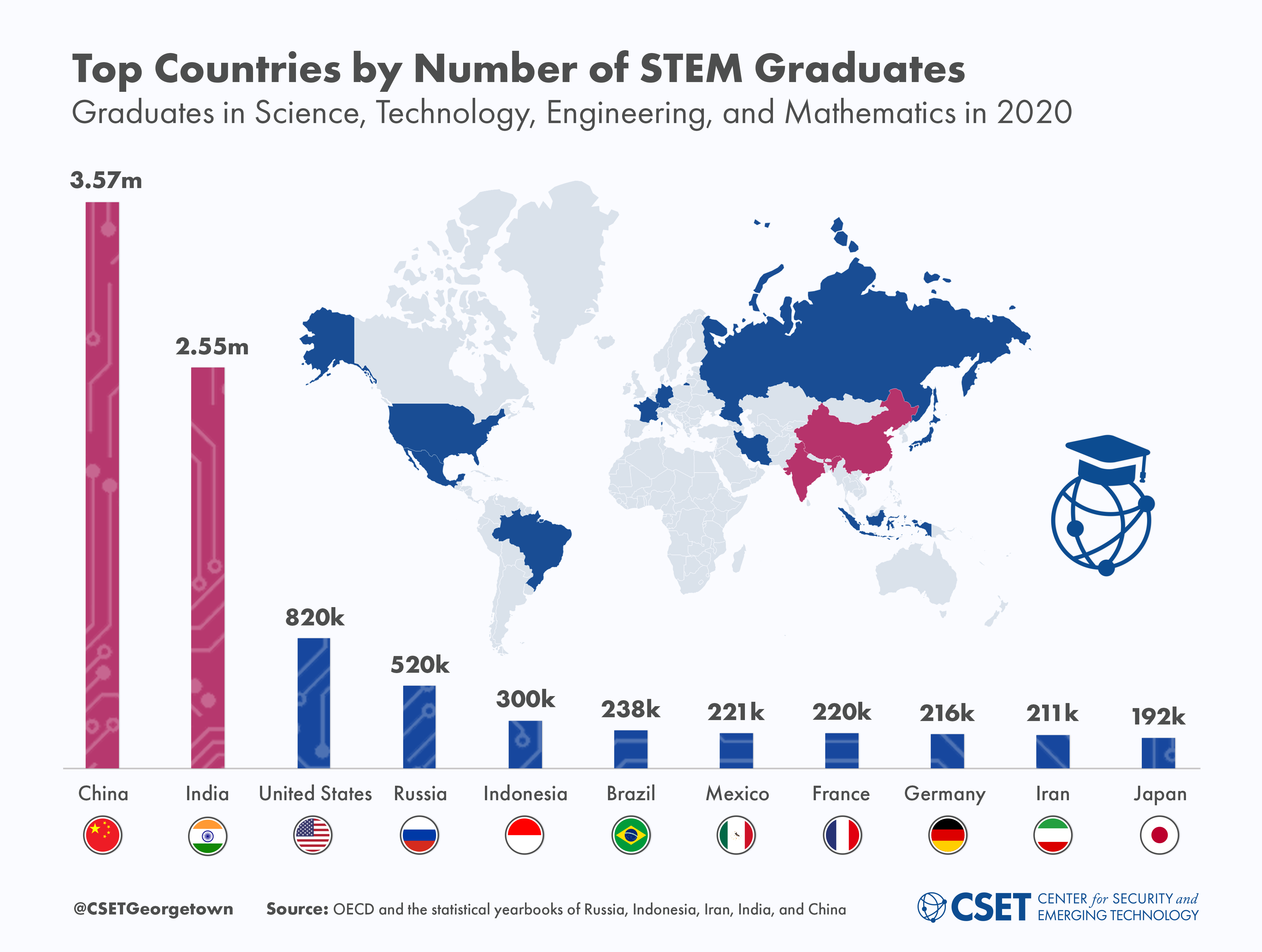

Figure 1 below shows the top eleven countries by number of STEM graduates in 2020. To perform this analysis, we draw on national education data and rely on the International Standard Classification Education framework developed by the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO), as well as the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development’s designation of STEM fields. We further describe our approach to this study in the “Methods” section below.

Figure 1 reveals a new shift in the global distribution of STEM graduates compared to the 2016 World Economic Forum report. The WEF report identified China, India, the United States, Russia, Iran, Indonesia, and Japan as the top seven STEM graduate-producing countries in the world. As of 2020, however, we find that Brazil and Mexico surpassed Iran and Japan in the number of graduates in STEM fields.

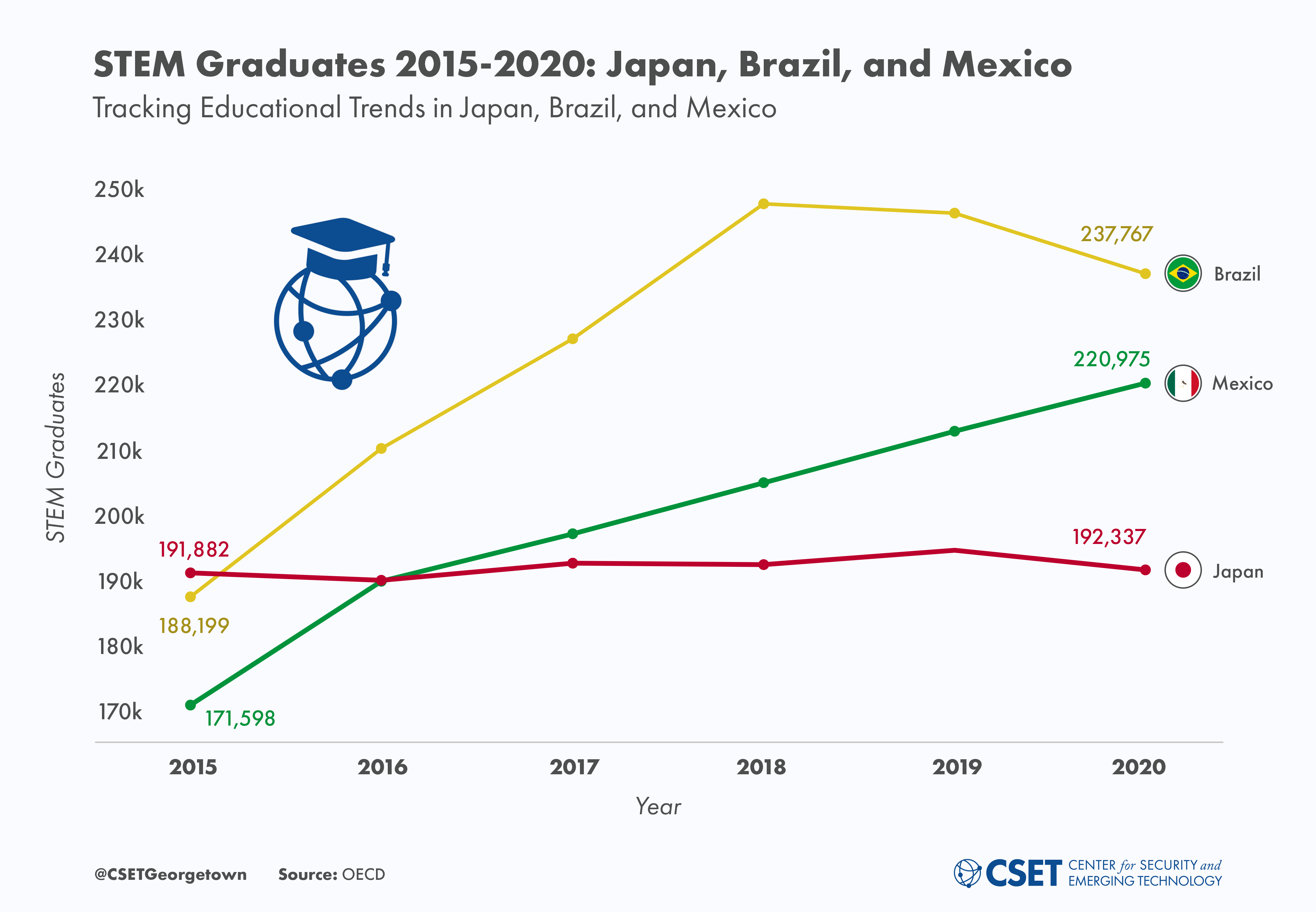

Following the boom in STEM education in Asia over the last several decades, the rapid growth of STEM graduates in China, India, Japan, and South Korea has received significant attention. Indeed, although each of these countries experienced tremendous growth in the number of STEM graduates over the past 50 years, new players like Brazil and Mexico are making significant strides in increasing the number of students graduating in STEM fields.

Figure 2 depicts the increase in STEM graduates in Brazil, Mexico, and Japan from 2015 to 2020. While Japan’s output of STEM graduates is relatively constant over the time period, Brazil’s number of graduates grew by ~26% and Mexico’s grew by ~30%. As higher numbers of STEM graduates have historically been an indicator of future economic growth, these strides in advancing STEM education suggest that Brazil and Mexico may be positioned for future success.

Comparing Percentage of STEM Graduates for Alternate View

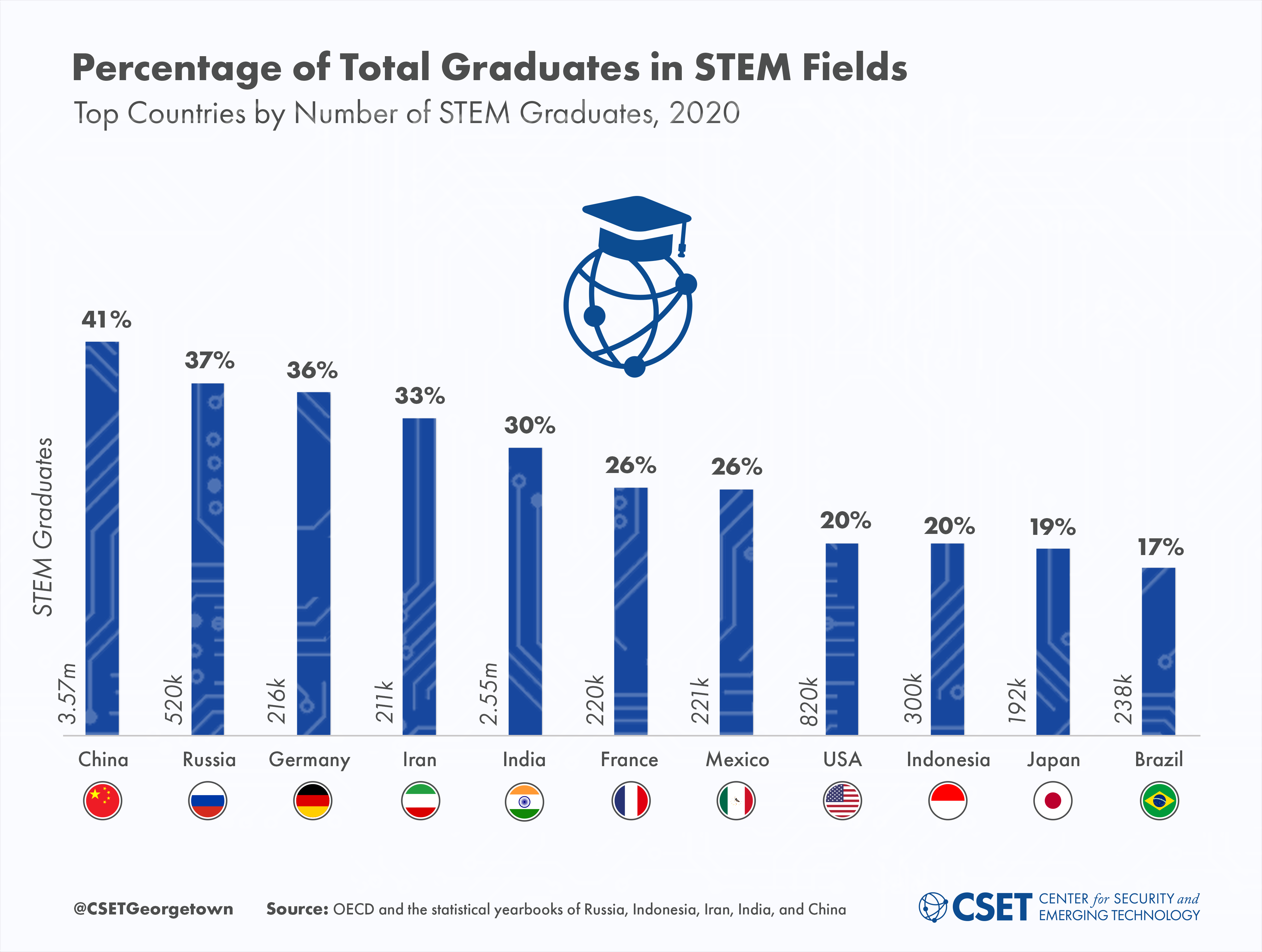

While the number of STEM graduates may serve as an indicator of future scientific and technological capacity, it fails to account for other differences in the STEM ecosystems of different countries. In Figure 3, we present the number of STEM graduates as a percentage of total graduates for each country to provide another perspective through which to understand the differences between countries’ STEM education ecosystems.

As shown in Figure 3, China leads in the percentage of students in STEM fields, with over 40 percent of college graduates obtaining a STEM degree. Not far behind, Russia, Germany, Iran, and India all produced more than 30 percent of graduates in STEM fields, with Germany closely rivaling Russia. Moreover, just 20 percent of graduates in the United States obtain a STEM degree, behind both Mexico and France.

Fostering U.S. Leadership in STEM

As the United States aims to maintain its leadership in talent in an increasingly competitive world, policymakers should foster STEM education at home and leverage its attractiveness to foreign talent from abroad. To expand the United States’ domestic supply of STEM graduates, policymakers should work to increase the accessibility of STEM programs at community colleges and 4-year institutions. Additionally, the United States should ensure that individuals with advanced degrees in STEM can continue to immigrate to the United States, as the recent EO endeavors to enable via H1-B processing and other reforms. As the United States seeks to attract talent from abroad, it is important to understand global shifts in the supply of STEM graduates. Particular attention should be paid to the rise of STEM talent in emerging market economies such as Mexico and Brazil. Recognizing these global shifts, the United States must continue to invest in building and attracting a highly skilled workforce, in order to maintain a thriving pool of STEM graduates for innovation, discovery, and national security. In doing so, the country will be better positioned to improve its competitiveness in critical, emerging technologies, and ultimately benefit from future progress in STEM.

More on Methods

For this analysis, we adopted widely-accepted standards for the classification of education statistics to collect and analyze our data. UNESCO and the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) define “STEM fields” as subjects in information and communication technology, engineering, construction, manufacturing, natural sciences, mathematics, and statistics. We adopted these fields, along with UNESCO’s standard classification of “tertiary education,” which designates the international equivalents of associate’s, bachelor’s, master’s, and doctorate degrees, to identify and count STEM graduates.