This blog post examines the first set of bio-relevant completed actions from the Biden administration’s October 2023 Executive Order on Safe, Secure, and Trustworthy Development and Use of Artificial Intelligence, which were due 180 days after the order’s signing.

The Biden administration’s October 2023 Executive Order on the Safe, Secure, and Trustworthy Development and Use of Artificial Intelligence (EO on AI) put forth a number of new provisions to better understand and reduce the potential for AI to enable biological risks which we described in our initial summary of the EO’s biosecurity-related sections.

In the months since the executive order was signed, various government agencies and responsible entities have been working through the first round of action items, which were due 180 days after the order’s signing. While these efforts represent great progress, they have also brought new questions and challenges to the surface. On June 6, 2024, CSET held a webinar with expert panelists Steph Batalis, Sarah R. Carter, and Matthew E. Walsh, and moderated by CSET’s Vikram Venkatram, to break down where things stand now.

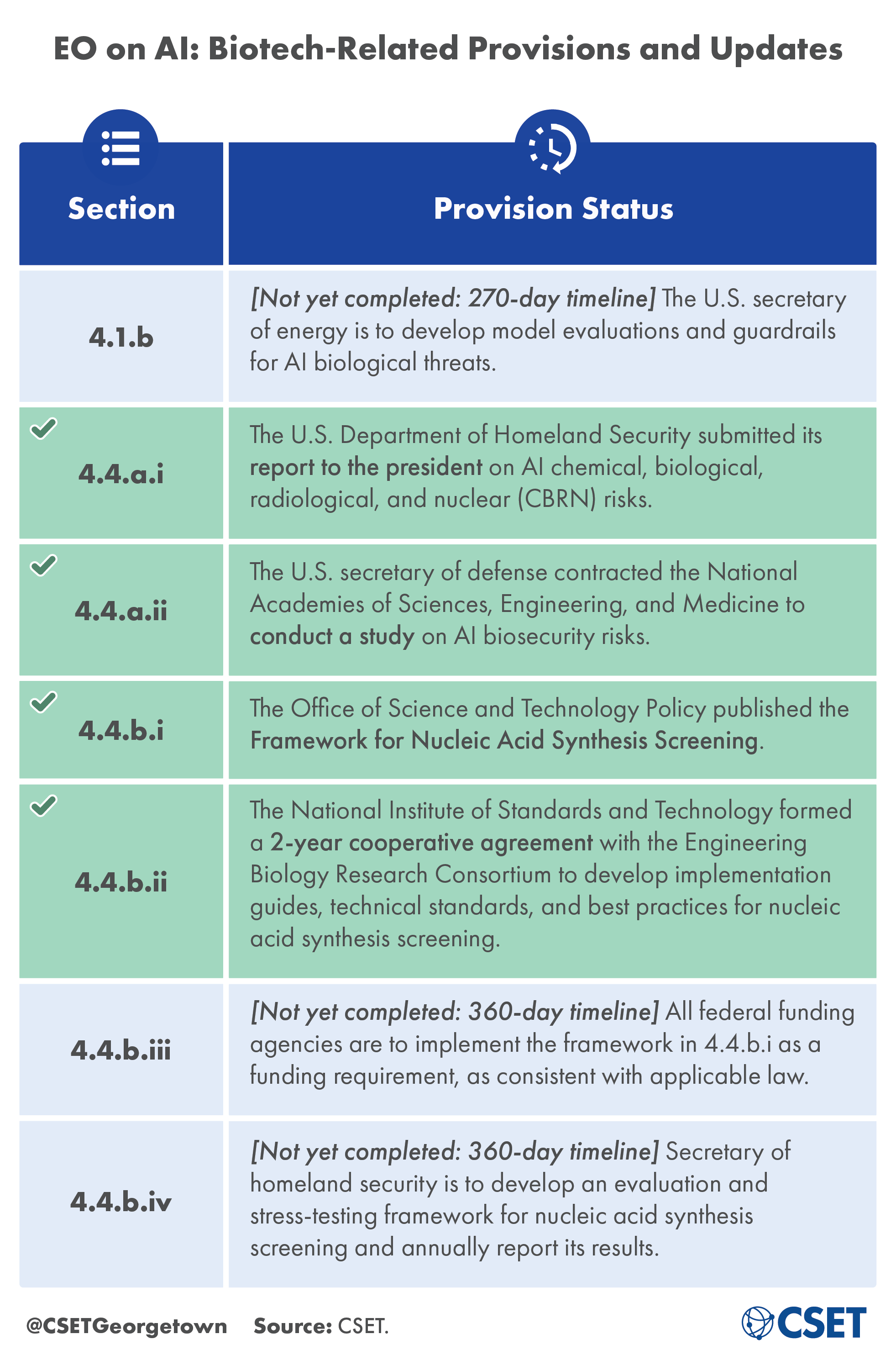

Below, we provide the EO’s major biosecurity-relevant updates, accompanied by a summary of our panelists’ takeaways regarding what they view as the EO’s most notable accomplishments, lessons learned from the first 180 days, and outstanding implementation challenges and next steps.

Updates on 4.4.a.i and 4.4.a.ii: Required Studies and Reports

Much remains to be understood about how AI could enhance or mitigate biological risks. Given the extremely rapid advancement of AI in the life sciences, addressing these open questions is critical to identifying where oversight is needed and in designing appropriate safeguards. To that end, two of the studies requested by the EO on AI have made major progress in the first 180 days. To fulfill section 4.4.a.i, the U.S. Department of Homeland Security released its report to the president examining trends in AI, the potential to misuse AI to develop or produce CBRN threats, and how AI could help to counter these same threats. The study required by section 4.4.a.ii is also underway, as the secretary of defense has contracted NASEM to examine generative AI models trained on biological data, the potential for models to reduce biorisk, and the national security implications of U.S. government-owned training datasets. NASEM has selected a committee of experts to conduct the analysis, and committee meetings began in June 2024.

From the Panel:

According to CSET’s panelists, the inclusion of these requested reports is a major strength of the EO’s approach, and a sign that the administration recognizes the complexity of AIxBio policy. To Steph Batalis, this inclusion reflects an acknowledgement that “there are some things that are ready to implement…and there are other areas where it’s important to do some more research and ask some more questions.” While the conversation around the EO has largely been focused on risk, the panelists agreed with Sarah Carter’s point that “it can’t just be a risk kind of analysis,” and that future assessments and actions will also need to consider AI’s potential benefits for the life sciences.

To the panelists, it was clear that the studies contracted by the EO on AI will need to measure many different factors, not just a few. One challenge will be to ensure that assessments identify and disambiguate the different types of biological risk posed by AI systems. Different types of AI models, users, and scenarios all present different types of risk, which require different solutions. For example, subject-specific AI systems can enable different types of users and outcomes than more general-purpose chatbots.

A second challenge is that studies need to account for both what the models themselves can do, and how users might use them—both of which are challenging to evaluate. Matthew Walsh described various types of assessments, and emphasized that it is important to think carefully about what each of these methods does and does not tell us: “What are the types of questions we want to be asking? And what do we want to be using the results for?” Critically, all three members of the panel emphasized that these studies should be comparative—they should test what users are capable of with and without access to AI tools. Matthew Walsh stressed the need for these studies to provide actionable information to impact policy decisions, including determining public access to the technology.

Updates on 4.4.b.i and 4.4.b.ii: Nucleic Acid Synthesis Screening

Synthesized nucleic acids—DNA or RNA molecules with a specific customer-provided sequence—are commonly used for a range of research purposes but could be misused in certain scenarios. Screening the customers who are allowed to order synthesized nucleic acids, the sequences of nucleic acids themselves, or both could be one way to mitigate possible misuse. Previous screening measures, including commitments from commercial providers and a screening framework from the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), were voluntary and nonbinding. The executive order implements a federal screening requirement for the first time: establishing that any research projects receiving federal research funding will be required to procure synthesized nucleic acids from companies that follow screening guidelines. The Office of Science and Technology Policy (OSTP) established those guidelines in the Framework for Nucleic Acid Synthesis Screening as required by EO section 4.4.b.i, and NIST is currently working with the Engineering Biology Research Consortium (EBRC) to engage experts, industry, and other stakeholders to develop technical screening standards and best practices in keeping with 4.4.b.ii.

From the Panel:

While the executive order marks the first actual U.S. requirement for nucleic acid synthesis screening, the panelists explained that the new mandate is the result of several years of effort from a broad community of researchers, biosecurity experts, and synthesis providers. Sarah Carter illustrated this foundation by pointing out past efforts, including a 2015 report from the Venter Institute assessing HHS’ screening guidance and the efforts to update the guidance in 2023, previous U.S. government initiatives to resolve technical challenges like IARPA’s Fun GCAT program, and a suite of practices that had already been voluntarily developed and adopted by DNA synthesis providers.

The new screening requirement represents a long-awaited step forward, but the panelists recognized that there will be implementation challenges. Notably, panelists agreed that deciding which nucleic acid sequences to screen for—those commonly called “sequences of concern” or SOCs—is a tougher question than it may seem because the risk associated with a particular sequence depends on the context in which it is used and may not be immediately clear. As Steph Batalis explained, “figuring out where and how to draw that line is a really big question.” Matthew Walsh added that not only is it important to establish the processes and infrastructure to develop these screening measures, but that it will be equally important to continually update them to adapt to technological advances. In addition to the challenge of defining SOCs, it’s also difficult to decide which users count as having a “legitimate use” for a specified sequence and thus should be allowed to order it. According to Sarah Carter, “there’s very few resources about how those decisions should be made,” even though a significant portion of flagged orders involve some element of customer screening.

Next Steps

As our panelists made clear, there is more work to do related to the EO on AI and its impact on biorisk. Some action items outlined in the EO on AI remain outstanding, with associated deadlines at the 270-day and 360-day marks (see Table of Biotech-Related Provisions). The already-completed tasks have also raised some questions that still need to be answered. For example, it remains to be seen how the studies requested by the EO will account for the many different types and sources of biological risk. Similarly, the new nucleic acid synthesis screening framework will need to consider how best to screen customers, how to draw the line between sequences of concern and not of concern, and how to ensure that policies can be updated as technology improves.

What is clear is that the EO on AI is forming a foundation for future policies governing AI and biological risk. Both the required studies and the requirement for a nucleic acid synthesis screening are creating a starting point to build regulations and oversight for AI-related and non-AI-related biorisk. Continuing to identify challenges, and asking and answering the questions brought about by this effort, will help to ensure the success of these future policies.

To see how other provisions from the EO on AI are progressing, check out CSET’s AI EO tracker.