Introduction

The Chinese Communist Party (CCP) believes it is engaged in a global struggle for China’s “image sovereignty” (形象主权 xingxiang zhuquan).[1] Party leaders recognize that “the main battlefield for public opinion” is on the internet, and are adamant that “the main battlefield must have a main force” (Central CAC, April 4, 2017). For China, that force is embodied in an array of “internet commentators”—trolls tasked with artificially amplifying content favorable to the CCP. Their mission is to “Implement the online ideological struggle” (落实网络意识形态斗争; luoshi wangluo yishi xingtai douzheng).[2] Their tactics are well-known to anyone who has spent time on the internet: “Quickly and accurately forward, like, and comment on relevant information on Weibo, blogs, websites, forums, and post bars, to effectively guide online dynamics” (Huailai County CAC, 2020). Still, English-language information about China’s internet trolls remains discordant and contradictory.[3]

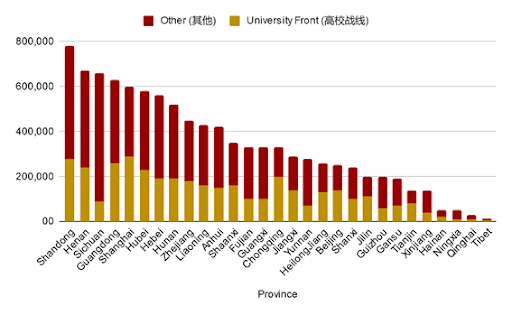

This article illuminates the shifting size and mission set of the forces behind China’s struggle to control online public opinion. It finds that, in addition to 2 million paid internet commentators, the CCP today draws on a network of more than 20 million part-time volunteers to engage in internet trolling, many of whom are university students and members of the Communist Youth League (CYL; 共产主义青年团, gongchan zhuyi qingnian tuan). It concludes that although internet commentators are primarily concerned with shaping China’s domestic information environment, they are growing in number, and the scope of the Party’s public opinion war (舆论战; yulun zhan) is broadening to include foreigners.

Raising China’s Internet Troll Army

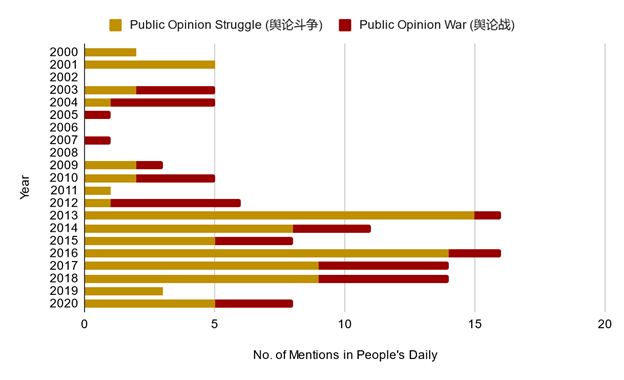

Shortly after taking office in 2013, China’s paramount leader Xi Jinping began a drastic shift in the CCP’s approach to governing cyberspace.[4] The CCP had experimented with public opinion management throughout the 2000s and early 2010s, with local and provincial Party committees establishing teams of several hundred commentators (Hefei Municipal Propaganda Department, May 24, 2006; Gansu Provincial CAC, January 20, 2010; Zhejiang Provincial CAC, November 30, 2012). At his first Propaganda and Ideological Work Conference as CCP General Secretary in 2013, Xi emphasized the importance of China’s “public opinion struggle” (舆论斗争; yulun douzheng) and stressed the need to “tell Chinese stories well” (China Media Project, September 24, 2013). That fall, the CCP announced the “seven baselines” (七条底线; qi tiao dixian), which became the foundational political and moral principles underscoring Chinese censorship (China Media Project, August 27, 2014).

The most momentous shift in China’s internet ecology came in 2015. After a sweeping ban on foreign VPNs, the Ministry of Education and the Central Communist Youth League issued a notice requiring Chinese universities to recruit teams of network commentators, called “network civilization volunteers” (网络文明志愿者; wangluo wenming zhiyuan zhe), and mandated quotas commensurate with the number of students enrolled in each province (China Digital Times: January 19, 2015, January 20, 2015). The guidelines began with modest requirements, remanding teams of commentators that represented just 0.5-1.5 percent of each university’s student body. But in September the Central CYL released new guidance clarifying that Provincial CYLs would have to supply 10 million volunteers—3.8 million of whom were to be students at Chinese colleges and universities.[5] The effect was to raise an army of internet trolls at breakneck speed. In Zhejiang province, what began as a team of 800 commentators in 2012 ballooned to more than 500,000 in 2016 (Zhejiang Provincial CYL, May 5, 2016). Contemporary reports from CYLs in Anhui, Guangdong, and Yunnan indicate similar surges and reveal that each manage hundreds of thousands of commentators, consistent with the Party’s requirements.[6]

Today, the CCP relies on an expansive network of more than 20 million “network civilization volunteers” to serve as “an ‘amplifier’ of positive online voices, a ‘collector’ of online public opinion information and a ‘reducer’ of negative voices on the Internet.”[7] They operate in concert with a professionalized corps of 2 million internet commentators (评论员; pinglunyuan), employed directly by Cyberspace Affairs Commissions (CAC) and Propaganda Departments nationwide (China Brief, January 12).[8] By drawing on complementary systems of “professional” and “grassroots” internet trolls, the CCP harnesses the organic nationalism of young Chinese netizens while maintaining a tight grid of hired hands capable of responding to public opinion “emergencies.”

Defending Forward on Social Media

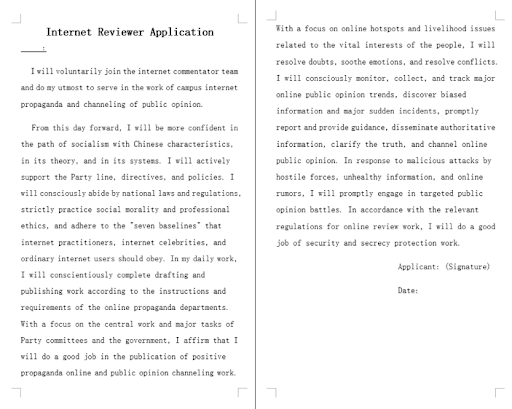

Although paid commentators tend to attract more attention from foreign analysts, the CCP’s network civilization volunteers form the backbone of its struggle to control public opinion inside and outside of China. The charters of network commentator teams at numerous universities specify that applicants should be CCP members, have high-quality writing ability, and acutely grasp the Party’s political theory and propaganda work (Guizhou University, September 29, 2017; Zhengzhou University of Light Industry, April 17, 2019).[9] A list of 100 volunteers mobilized by a college in Anhui province reveals that the average volunteer is just 19 years old.[10] They are mechanics, nursing students, preschool class monitors—all politically zealous young Chinese who, in their spare time, are supposed to “stop the spread of various illegal and harmful information on the internet, and contribute to the construction of a clean cyberspace.”[11]

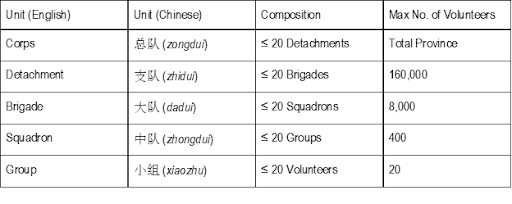

Despite their youthfulness, China’s teams of internet trolls are surprisingly militant in character and structure. The budget justification documents of CYLs, CACs, and Propaganda Departments routinely refer to internet commentators as a “young cyber army” (青年网军; qingnian wang jun) and describe them as a “reserve force” capable of “resolutely resisting false statements and rumors, and fighting online public opinion wars.”[12] In Shandong province, for example, volunteers are organized into a five-tier command structure designed to “resolutely resist, actively refute, and actively report erroneous statements on the internet”:[13]

Each commentator team follows unique guidelines, but volunteers are generally asked to post between 1–25 comments per month and are governed by a merit-based point system that determines whether they may be promoted or fired.[14] They coordinate closely with paid internet commentators, internet companies, Public Security Bureaus, and CACs to “monitor online speech and discover illegal activities” so that “uncivilized behaviors in cyberspace and real space will have nowhere to hide” (Legal Evening News, November 20, 2020). The end goal is to “create a diversified network team consisting of online commentators, public opinion officers, and network civilization volunteers” that are “seamlessly connected.”[15]

The Party views its deployment of these volunteers as a defensive measure against hostile foreign forces looking to smear the good name of China. Yet applications for these positions clarify that volunteers are expected to launch “targeted public opinion struggles” in response to unflattering web content that the CCP views as an attempt to “falsely split the motherland” (PLA Daily, May 2017). They also participate in “public opinion actual combat drills” (舆情实战演练; yuqing shijian yanlian), which simulate PR crises and train commentators in online public opinion management, press relations, and “credibility restoration” (Huzhou Municipal CYL, 2019; China Youth Net, July 26, 2015; People’s Daily, May 19, 2017).

Waging Global Public Opinion War

Chinese netizens bear the brunt of the CCP’s online influence operations. Based on data from CYLs in four provinces, the Party likely employs at least 120 “network civilization volunteers” for every 10,000 Chinese internet users.[16] They have harassed Weibo users into silence on important social issues and flagged—at a minimum—tens of thousands of Chinese social media accounts for company censors to close based on moral and ideological grounds (The Diplomat, April 3, 2020; RestofWorld, October 22, 2020). As the CCP has made strides in quashing dissent at home, it has also pivoted toward shaping public opinion in other countries—and seems to be growing more comfortable with using its army of internet trolls as a weapon of foreign influence.

CCP offices and state media outlets are not shy about describing what they perceive to be a “public opinion war” (舆论战; yulun zhan) with the United States, and they emphasize the value of internet commentators in winning that war. The phrase originated as a way of describing China’s longstanding, asymmetric approach to information warfare, even before the internet became mainstream in China (China Brief, August 22, 2016). However, in the Xi era, Chinese authors have been more forthright in describing an actual, ongoing conflict with much of the Western world, and are applying the lens of “public opinion war” to cyberspace (China Brief, September 6, 2019). Various issues of New Media, the journal of the Central Cyberspace Affairs Commission, have discussed how China should win a “soft power competition in which countries seize international discourse power and lead international public opinion.”[17] Observers in the People’s Liberation Army believe that, “in the face of the powerful online public opinion manipulation capabilities of the United States and other Western countries,” China should “construct a network discourse system with the characteristics of our military” to “exert public opinion influence on the enemy and even third-party countries in the wartime online public opinion struggle” (Military Reporter, May 2017). Newspapers such as Xinhua and People’s Daily likewise view themselves as being on the front lines of a “China-U.S. Public Opinion War” (中美舆论战; zhong mei yulun zhan), and—by their own admission—seek to frame foreign audiences’ perceptions of current events (most recently including COVID-19 and trade tensions) in ways that benefit the state and Party (People’s Daily, January 6, 2018).[18] The task before internet commentators is to amplify that content and to refute foreigners who would question or criticize the Party’s worldview.

Considering the immense capacity for trolling it has developed over the past six years, the CCP so far seems to have directed its army of internet commentators relatively sparingly against foreign social media networks. Internet commentators have selectively mobilized around China’s core interests, such as promoting the Hong Kong National Security Law and China’s handling of COVID-19, as well as most recently defending against allegations of forced labor in Xinjiang (WSJ, October 16, 2019; NYT, December 19, 2020; March 29). For example, the Guangdong Provincial CYL operates a “young cyber army team consisting of 100 internet commentators, nearly 5,000 internet propagandists, and over 800,000 internet civilization volunteers” who “take the initiative to speak up during major public opinion events.”[20] The organization lists two examples of when volunteers spoke up in 2018: supporting China’s interpretation of the Hong Kong Basic Law and opposing deployment of the THAAD missile defense system in South Korea.

Conclusion

By many accounts, the CCP is failing in its mission to sway global public opinion of China. The country’s botched handling of the COVID-19 outbreak; military aggression in the Himalayas and maritime Southeast Asia; and ongoing detention of more than a million Uyghurs have placed indelible stains on its reputation abroad (China Brief, December 6, 2020; Pew, March 4). On the few occasions that the Party has mobilized trolls to meddle on foreign platforms, they have been thwarted—with disastrous consequences for its broader propaganda apparatus.[21] Simply put, by starting to swing around its bully pulpit, the CCP has spurred foreign social media platforms—already on guard against domestic and foreign disinformation campaigns—to respond forcefully, hurting the Chinese state’s global reputation and its ability to “tell Chinese stories well.”

But it would be a mistake to discount the CCP’s struggle to control foreign public opinion. On the contrary, China’s global influence apparatus is learning and evolving, as it has done for the past two decades. The Central CAC is studying how information propagates in the American media environment, and is learning to maximize the reach of its propaganda by studying NowThis viral videos, Cambridge Analytica’s microtargeting strategies, and Russia’s disinformation campaign during the 2016 election (Central CAC, January 23, 2017; Central CAC, January 23, 2017). The Party has experimented with large-scale botnets to compensate for language deficiencies among its internet trolls, and communication experts are identifying ways to “choose information sources intelligently, hide opinions in facts, package content carefully, and dilute ideological colors” (ChinaTalk, October 29, 2020; New Information, April 4, 2020).

State-owned news agencies are likewise beginning to recognize that the heavy handed approach to propaganda at home—literally “report the good, but not the worry” (报喜不报忧; bao xi bu bao you)—is counterproductive abroad, because it only invites criticism from skeptical consumers (People’s Daily, January 10, 2018). Instead, they have begun “replacing the original propaganda tone with the language organization of ‘storytelling,’” so as to “reduce the traces of propaganda, allowing foreign audiences to subtly change their impression of China, without causing disgust” (People’s Daily, January 10, 2018). The bottom line is that China’s internet trolls are here to stay. And if the past twenty years are any indication, foreigners should expect the CCP’s influence operations to continue growing in size and sophistication, alongside the objectives of its public opinion war.

Notes

[1] The term refers to a country’s right to manage its international brand or reputation. Chinese authorities believe they are the target of an unfounded smear campaign on behalf of the United States—an “information opium war” (信息鸦片战; xinxi yapian zhan) (People’s Daily, January 2018; China Civilization Net, 2014).

[2] For the exact quote, see Songjiang District CYL, 2019. For other examples of responsibilities assigned to network commentator teams, see Huadu District CYL, 2018; Huzhou Municipal CYL, 2019; Foshan Municipal CYL, 2019; or Yunnan Provincial CYL, 2021. For further analysis of China’s public opinion management, see Harvard University, 2017; and Atlantic Council, December 2020.

[3] See differing conclusions about the number of trolls and whether they are paid in Harvard University, May 2013; Business Insider, October 18, 2014; Foreign Policy, August 25, 2016; VOA, October 7, 2016; and New York Times, October 19, 2020. The myriad labels for China’s internet trolls often grow out of internet subcultures and are sometimes applied in bad faith by political opponents (SupChina, November 2017). To make matters more complicated, the common, formal name for web trolls—“commentators” (评论员; pinglunyuan)—is synonymous with being a professional newspaper columnist or editorial writer.

[4] See analysis in Cyber Defense Review, 2017; Guardian, June 2018; The Atlantic, 2018; and USCC, 2020.

[5] Central Communist Youth League 共青团中央, “Gongqingtuan zhongyang wenjian” 共青团中央文件 [Communist Youth League Central Document], September 2015, https://web.archive.org/web/20201205194641/http://www.hgtc.org.cn/admin/webedit/UploadFile/201531113553606.pdf.

[6] Anhui Provincial Committee of the Communist Youth League 共青团安徽省委员会, “Guanyu renzhen xuexi xuanchuan guanche sheng di shisi ci tuan dai hui jingshen de tongzhi” 关于认真学习宣传贯彻省第十四次团代会精神的通知 [Notice on earnestly studying, publicizing and implementing the spirit of the 14th Provincial Youth League Congress], 2017, https://web.archive.org/web/20201204233703/http://www.ahgcjs.com/u/cms/www/201712/26162814bzog.pdf.

Guangdong Provincial Communist Youth League 共青团广东省委员会, “Guanyu yinfa tuan sheng wei shisan jie wu ci quanhui youguan cailiao de tongzhi” 关于印发团省委十三届五次全会有关材料的通知 [Notice on Printing and Distributing Relevant Materials of the Fifth Plenary Session of the 13th Provincial Committee of the Communist Youth League], 2016, https://www.gdcyl.org/Article/UploadFiles/201609/2016090915373995.pdf.

Yunnan Provincial Communist Youth League 共青团云南省委员会, “Bumen zhengti zhichu jixiao zi ping baogao” 部门整体支出绩效自评报告 [Self-evaluation report of department’s overall expenditure performance], 2018, https://web.archive.org/web/20201123203525/http://webcache.googleusercontent.com/search?q=cache%3AuktUNmpKBowJ%3Ayn.youth.cn%2Ftz%2F201908%2FW020190820549895713891.xls+&cd=1&hl=en&ct=clnk&gl=us.

[7] Jiangxi Provincial Party Committee School Department of the Communist Youth League 共青团江西省委学校部, “Zhongguo gongchandang, zhongguo gongchan zhuyi qingnian tuan jian shi gangyao” 中国共产党、中国共产主义青年团简史纲要 [Outline of the brief history of the Communist Party of China and the Communist Youth League of China], April 2019, p. 188, https://web.archive.org/web/20201205202348/http://tw.jxcfs.com/_mediafile/tw/files/20190416120254543.pdf.

[8] Ibid.

[9] Guangxi University of Science and Technology Committee of the Communist Party of China 中共广西科技大学委员会, “Xuanchuan bu wen jian” 宣传部文件 [Propaganda Department Documents], 2013, https://perma.cc/5MSX-G5K6.

Zhejiang University Committee of the Communist Party of China 中共浙江大学委员会, “Zhonggong zhejiang daxue weiyuanhui guanyu shenru xuexi guanche quanguo gaoxiao sixiang zhengzhi gongzuo huiyi jingshen de tongzhi” 中共浙江大学委员会关于深入学习贯彻全国高校思想政治工作会议精神的通知 [Notice of the Zhejiang University Committee of the Communist Party of China on In-depth Study and Implementation of the Spirit of the National Conference on Ideological and Political Work in Colleges and Universities], 2019, https://web.archive.org/web/20201206012749/http://grs.zju.edu.cn/attachments/2017-01/01-1483941751-111945.pdf.

[10] Chizhou Vocational and Technical College 池州职业技术学院, “Chizhou zhiye jishu xueyuan qingnian wangluo wenming zhiyuan zhe gugan duiwu xinxi huizong biao” 池州职业技术学院青年网络文明志愿者骨干队伍信息汇总表 [Summary of Information on the Backbone Team of Young Network Civilized Volunteers of Chizhou Vocational and Technical College], 2020, https://web.archive.org/web/20210205200437/http://www.czvtc.edu.cn/uploads/file/20200707/20200707092617_76535.pdf.

[11] Central Committee of the Communist Party of China and the State Council 中共中央国务院印发, “Zhong chang qi qingnian fazhan guihua (2016-2025 nian)” 中长期青年发展规划(2016-2025年)[Medium and Long-term Youth Development Plan (2016-2025)], 2016, https://web.archive.org/web/20201205200538/http://www.jiazhangmooc.com/doc/4.pdf.

[12] Communist Youth League Committee of Xi’an University of Science and Technology 共青团西安科技大学委员会, “Guanyu zujian wo xiao qingnian wangluo wenming zhiyuan zhe duiwu, shenru tuijin qingnian wangluo wenming zhiyuan xingdong de tongzhi” 关于组建我校青年网络文明志愿者队伍、深入推进青年网络文明志愿行动的通知 [Notice on the formation of our school’s youth network civilization volunteer team and in-depth promotion of youth network civilization volunteer actions], 2015, https://perma.cc/73UW-LSMB.

Wuhan Municipal CAC, “Zhengti jixiao mubiao” 整体绩效目标 [Overall performance target], 2020, https://perma.cc/WR43-CBZD.

Weifang City Propaganda Department, “Xuanchuan bu 2019 niun gongzuo zongjie ji 2020 nian gongzuo jihua” 宣传部2019年工作总结及2020年工作计划 [Propaganda department’s 2019 work summary and 2020 work plan], 2020, https://perma.cc/67KS-YB5E.

[13] Licang District Committee of the Communist Youth League 共青团李沧区委, “Shenru tuijin qingnian wangluo wenming zhiyuan xingdong de tongzhi” 深入推进青年网络文明志愿行动的通知 [Notice on Deepening the Volunteer Action of Youth Network Civilization], 2015, https://perma.cc/Q5XW-3F54.

[14] Hunan Automotive Engineering Vocational College, “Wangluo wenming chuanbo zhiyuan zhe guanli banfa” 网络文明传播志愿者管理办法 [Measures for the Administration of Volunteers in the Communication of Internet Civilization], 2018, https://web.archive.org/web/20210205200702/http://www.zzptc.com/wenming/UploadFiles_9756/201810/2018102609583448.pdf.

[15] Publicity Department of Shangyi County Party Committee of the Communist Party of China 中共尚义县委宣传部, “Zhonggong shang yi xianwei xuanchuan bu 2019 nian bumen yusuan xinxi gongkai” 中共尚义县委宣传部2019年部门预算信息公开 [Publicity Department of Shangyi County Party Committee of the Communist Party of China’s 2019 Departmental Budget Information Disclosure], 2019, https://perma.cc/2RNP-QJXH.

[16] This estimate comes from comparing the average number of network civilization volunteers reported by Communist Youth Leagues in Anhui, Guangdong, Yunnan, and Zhejiang (489,000 volunteers) to the average number of internet users in those provinces, according to Knoema in 2016.

[17] Central CAC, Wangluo chuanbo 网络传播 [Internet broadcast] no. 164 (July 2017), https://web.archive.org/web/20210226231456/http://www.cac.gov.cn/wxb_pdf/201707wangluochuanbo.pdf.

[18] Central CAC, “Zhongguo xinwen jiang wangluo xinwen zuopin canping tuijian biao” 中国新闻奖网络新闻作品参评推荐表 [China News Awards Online News Works Participation Recommendation Form], June 2019, https://web.archive.org/web/20210226232118/http://www.cac.gov.cn/rootimages/uploadimg/1596117513438021/1596117513438021.pdf.

[19] The author queried the number of People’s Daily articles mentioning public opinion struggle or war between January 1, 2000 and December 31, 2020. See search results at http://data.people.com.cn/rmrb/.

[20] Guangdong Communist Youth League, “2018 Nian gongchan zhuyi qingnian tuan guangdong sheng weiyuanhui bu men juesuan” 2018 年共产主义青年团广东省委员会部门决算 [Final accounts of the Guangdong Provincial Committee of the Communist Youth League in 2018], 2018, https://perma.cc/T58U-24ZZ.

[21] Along with banning thousands of the CCP’s sockpuppet accounts, Twitter affixed permanent labels to Chinese state media outlets operating on its platform, yielding a significant drop in likes, shares, and retweets of their content (Twitter Safety, June 2020; China Media Project, January 18, 2021).