This is the third installment of a three-part data snapshot series. Read Part 1 & Part 2.

One way for large technology firms to expand their existing market power is through corporate investments. Companies like Alphabet, Amazon, and Microsoft (hereafter “Big Three”) rank among the most valuable corporations in the world, and each controls an expansive collection of assets, such as cash, computing infrastructure, and technical talent. By investing their excess resources in smaller companies, Big Three companies gain a stake in these fledgling firms, as well as potential influence over the deals, business models, and products they pursue. Incumbent firms can also acquire startups outright, subsuming their products and personnel into existing or new lines of business. Corporate investments can allow companies to expand their influence into adjacent sectors, particularly when used in combination with other strategies like infrastructure investments, workforce development programs, and open-source software ecosystems.

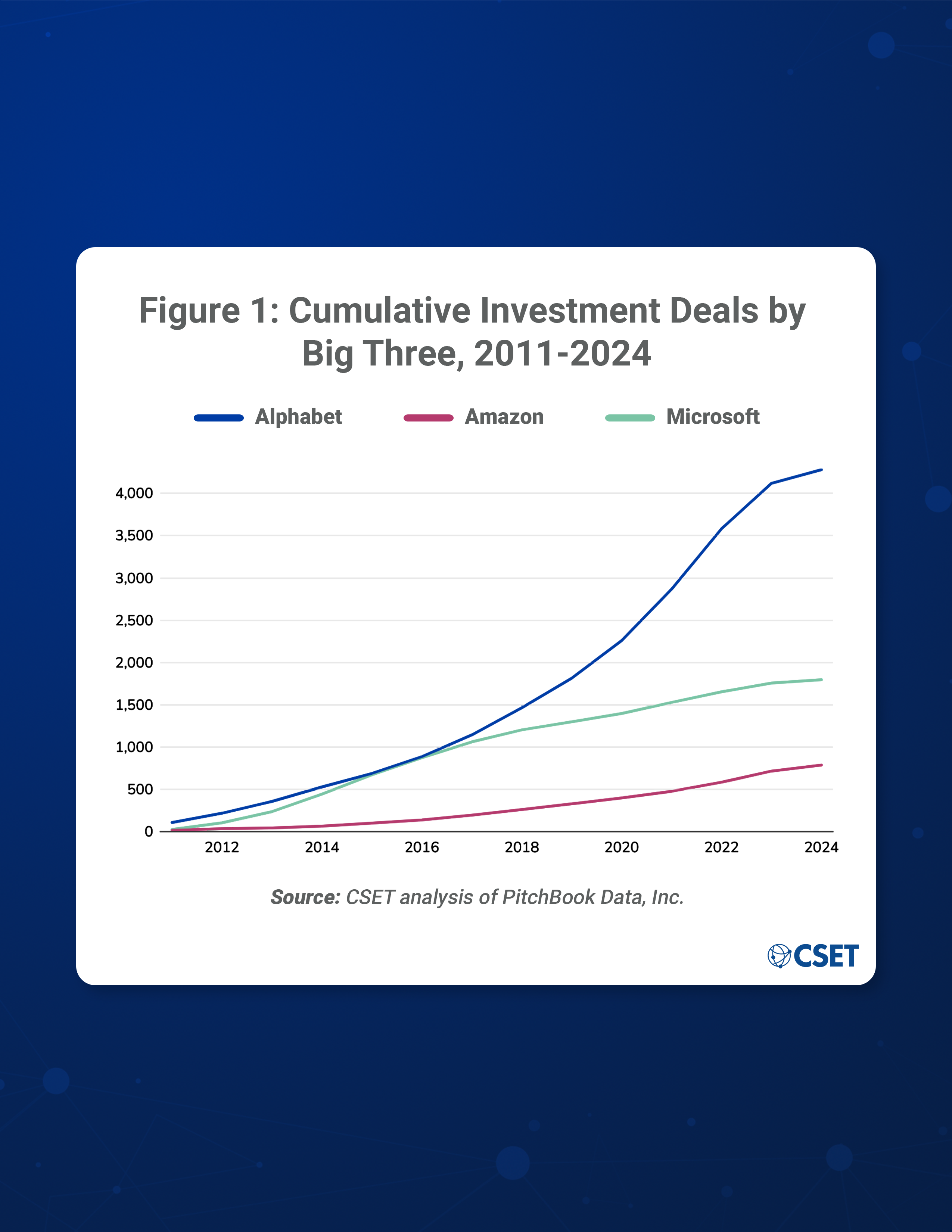

As seen in Figure 1, of the Big Three, Alphabet has the highest number of investment deals since 2011, with 4,281 transactions recorded by PitchBook. While Microsoft kept pace with Alphabet’s dealmaking through 2017, Alphabet then had a notable uptick in investment activity which has continued through today. Amazon has made comparatively few corporate investments, though its annual deals have increased slightly since 2014.

Figure 1: Cumulative Investment Deals by Big Three, 2011-2024

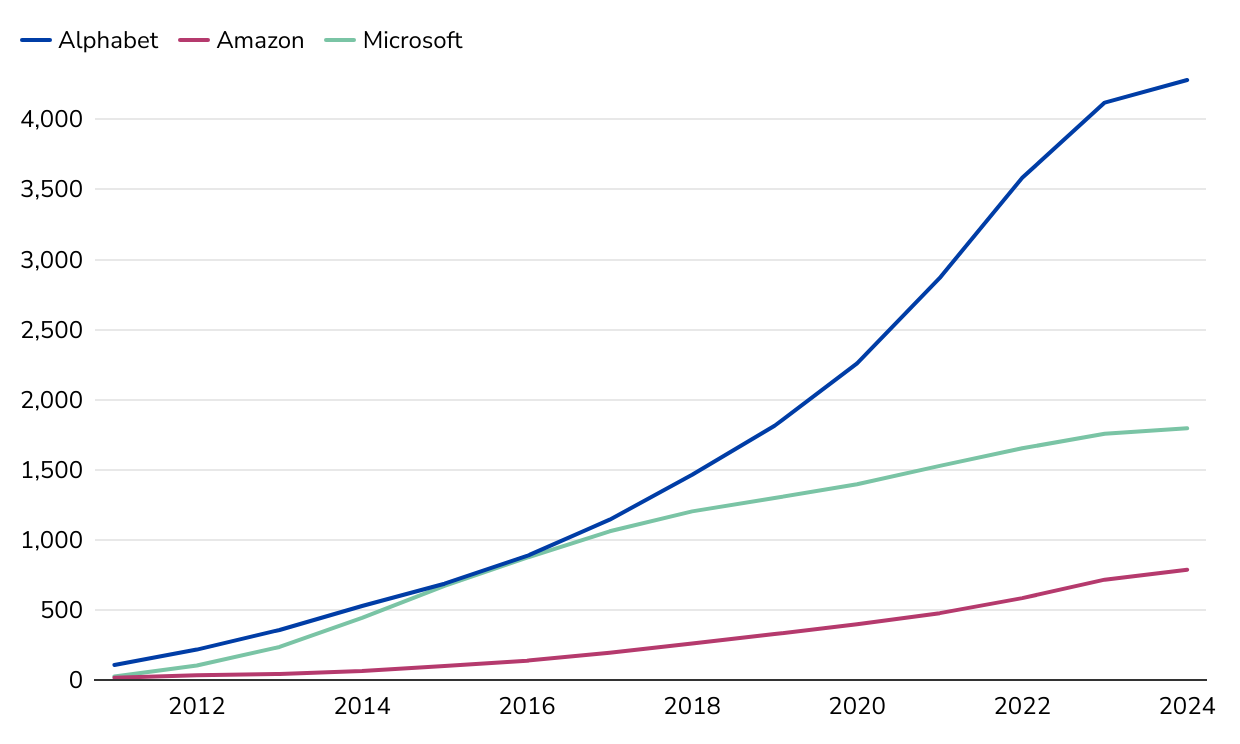

Figure 2 breaks down these investments by the location of the company targeted in each of the Big Three’s investments. While the Big Three have focused half of their investments on U.S. companies, we also see a substantial number of investments in companies based in the UK and Canada, as well as countries with rapidly growing tech sectors like India, China, and Brazil. In these high-growth economies, investments offer the Big Three opportunities to make inroads with fledgling companies that could one day emerge as industry leaders. The financial relationships established through these investments could also draw targeted companies into the investor’s cloud ecosystem. In such situations, the investor (Alphabet, Amazon, or Microsoft) would benefit from the equity secured through the deal, as well as from the addition of a long-term cloud customer.

Figure 2: Geographic Distribution of Big Three Investments by Investment Count, 2011-2024

These investments are made through a variety of avenues and may take a variety of forms. A substantial share (42%) of the Big Three’s global investments were made through accelerator or incubator programs, which are designed to help startups build out their ideas into working products, learn from mentors, and network with investors. The remaining 58% percent of transactions include mergers and acquisitions (M&A), venture capital investments (VC), and other deals such as convertible debt. For the purposes of this analysis, we will first examine this latter group of deals (non-accelerator investments) before turning to the former (accelerator investments).

Non-Accelerator Investments

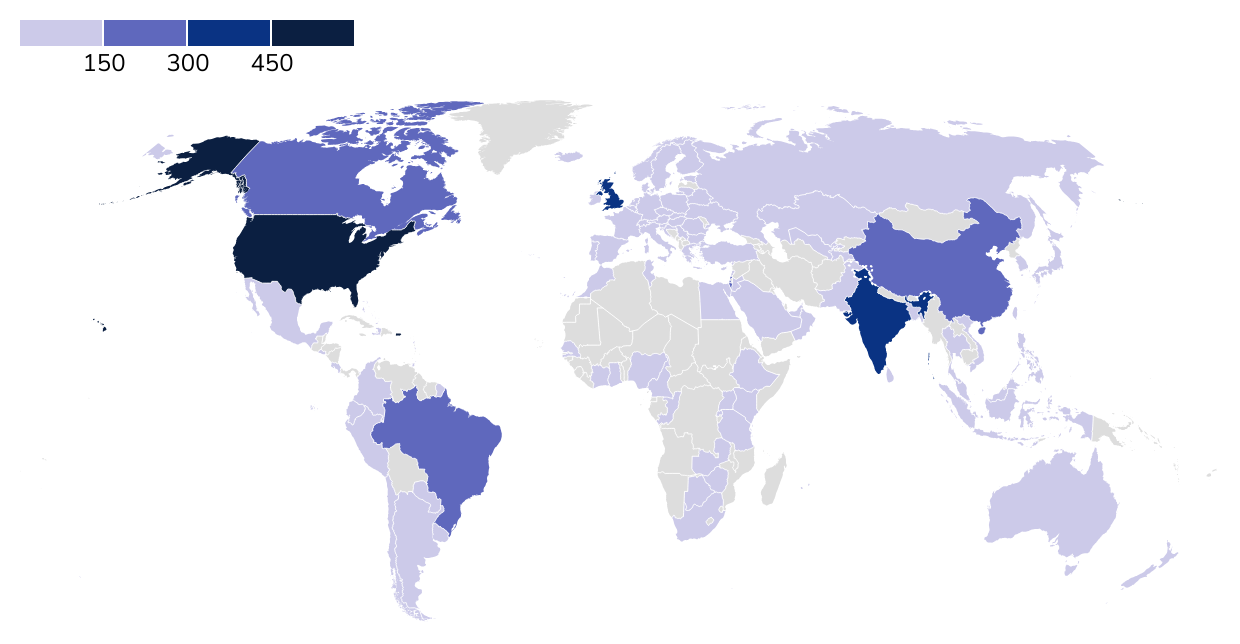

Our analysis found the two most common types of investments pursued by the Big Three were M&A transactions and VC deals. In M&A transactions, the incumbent acquires full control over the startup, subsuming its technology and talent into the acquirer’s larger operations. In VC transactions, the incumbent exchanges some of its own resources (cash, cloud credits, etc.) for a stake in the targeted firm, typically under the presumption that the firm will grow and the incumbent will see a high return on its investment. VC investments may target companies at different levels of maturity: first is the seed round, which usually involves a smaller amount of equity and lower valuations. Early-stage venture rounds—the next phase after seed rounds—involve more established VC firms offering more cash for more equity. Companies that are then able to consistently generate revenue may undergo later-stage venture rounds in order to secure more financing as they attempt to solidify their position within the market. It is worth noting that VC investments are typically subject to less regulatory scrutiny than M&A transactions.

As shown in Figure 3, Amazon and Microsoft have a different portfolio of investment activity than Alphabet. For Amazon and Microsoft, M&A transactions accounted for nearly a quarter of their non-accelerator investment portfolios. By contrast, M&A deals made up only 11% of Alphabet’s non-accelerator investments. Alphabet not only devoted a larger share of its investments to VC deals, but it also tended to direct those VC investments at younger companies—Alphabet made 64% of its VC deals in seed and early-stage rounds, compared to 57% for Microsoft and 55% for Amazon. These investment patterns suggest the Big Three are readily leveraging their existing capital to receive either direct or indirect stakes in a variety of companies.

Figure 3: Count of Deal Type of Big Three’s Non-Accelerator Investment Portfolios, 2011-2024

Accelerator Investments

Another way technology companies gain influence over fledgling companies is through “accelerator” or “incubator” programs, which are designed to help startups build out their ideas into working products, learn from mentors, and network with investors. These programs tend to target startups that have not yet developed a product or even proof of concept, though more mature companies may also participate. The activity of these startup-specific entities within the Big Three provides key insights into how these companies are marketing their ecosystems to newer and smaller companies.

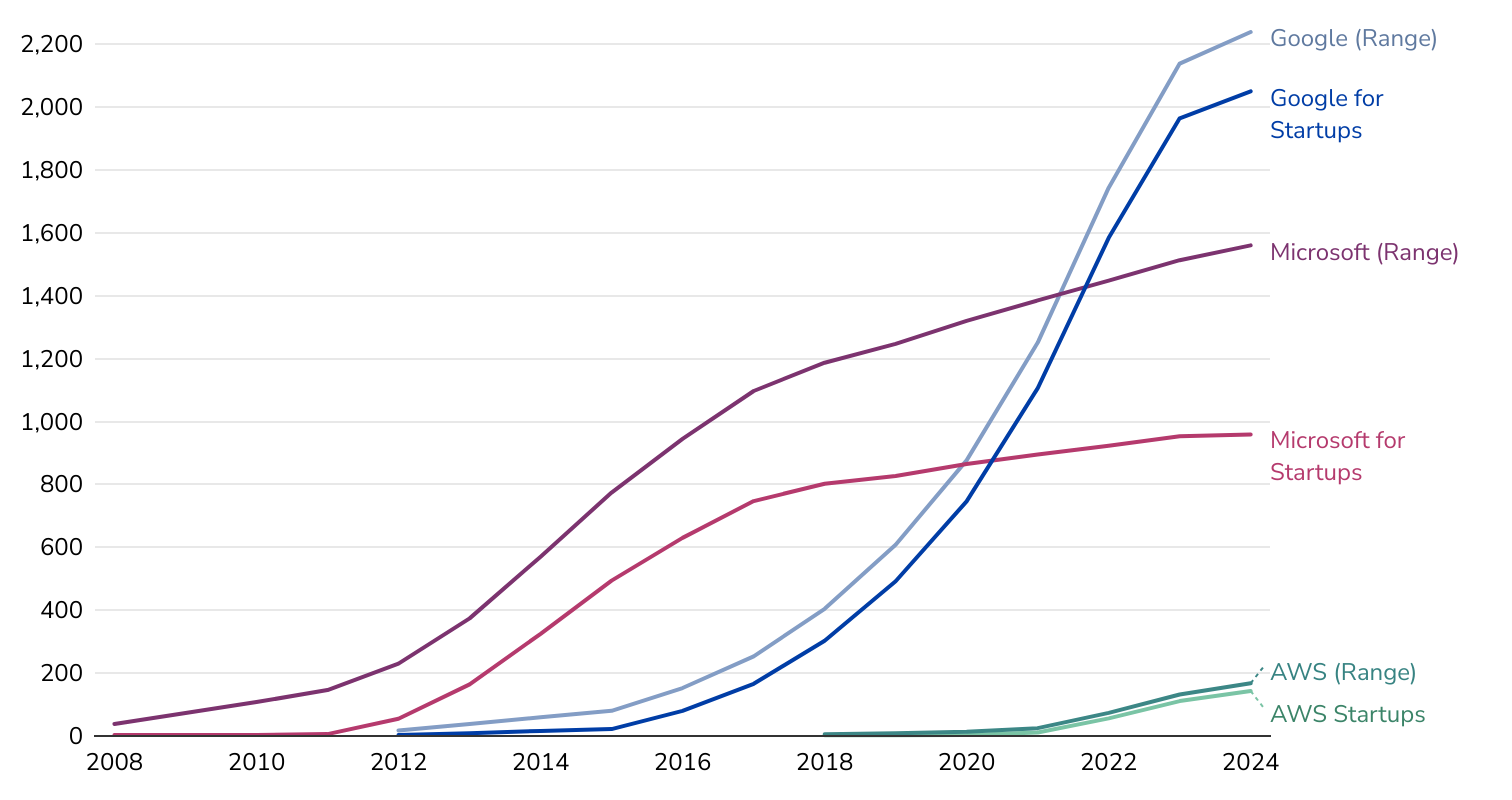

As shown in Figure 4, the Big Three have made extensive use of accelerator programs to build relationships with companies around the globe. Google for Startups has supported nearly 2,600 companies across 90 countries since 2012. Microsoft can be tracked in a similar way, and has supported over 1,100 companies across 59 countries since 2008. AWS Startups has been relatively less active, with 168 deals across 18 countries. It is notable that AWS Startups, which was founded in 2018, is also the newest of the three accelerator programs. While Amazon was likely offering similar start-up support prior to 2018, the fact that it did not create a standalone unit for this activity suggests the company did not prioritize these types of investments until more recently. By contrast, Microsoft for Startups was founded in 2008 (albeit with slow initial growth), and Google for Startups launched in 2012. Google began a massive campaign to increase its startup support in 2016, ultimately surpassing Microsoft’s accelerator investments around 2021.

Figure 4: Cumulative Big Three Accelerator Investments, 2008-2024

Note: Not all of these deals have dates associated with them. The range of missing values is shown through (Range) lines.

Some of these accelerator programs are explicitly designed to draw startups into the Big Three’s product ecosystems. For example, AWS offers $1 billion in cloud compute credits every year to startups if they build their companies on AWS. In certain industries, such as artificial intelligence, these cloud credits can be more valuable than cash. Such perks are a major draw for startups—on its website, Amazon claims that “96% of AI/ML unicorns run on AWS.” Both Google for Startups and Microsoft for Startups offer similar cloud computing and support services as well. Similar to workforce development programs and open-source software packages, these cloud deals offer distinct benefits to their participants while simultaneously luring and locking them into the Big Three’s product ecosystems.

AI Investments

As the world’s top providers of cloud computing services, the Big Three are especially attractive partners for AI companies. Developing and deploying AI tools requires massive amounts of computing power, and due to the high costs of computing hardware, many companies rely on cloud providers to access this infrastructure. As the compute requirements for leading AI models continue to grow, the Big Three are able to exercise more and more leverage over AI developers, with potentially negative implications for market competition, technological innovation, and national security. To understand how the Big Three are interacting with the AI industry, we examined their investments (both accelerator and non-accelerator) in AI companies. We identified AI companies using PitchBook’s Verticals classifications and keywords generated from the company description and augmented by PitchBook researchers.

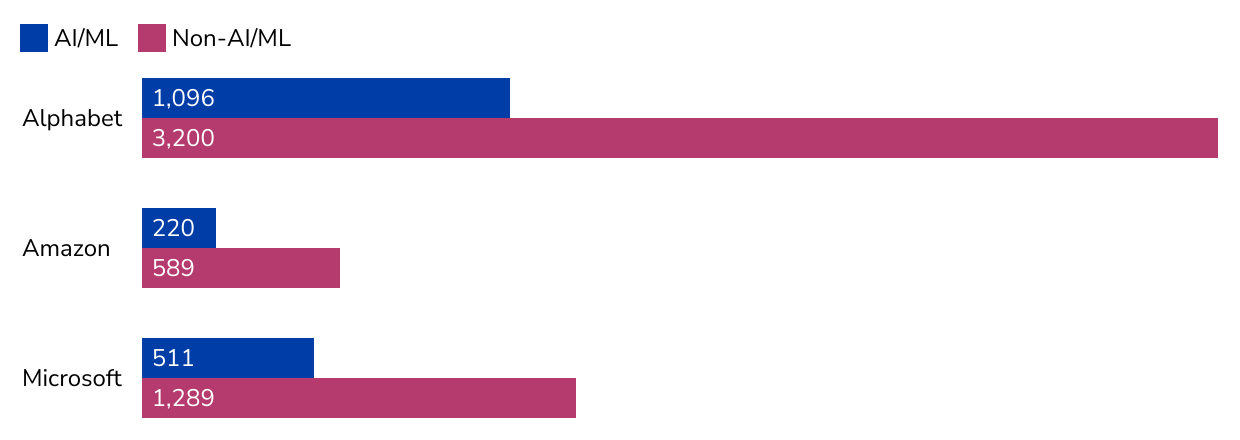

As shown in Figure 5, we found that Alphabet has had the most investments in AI companies, making nearly 1,100 investments in the AI sector between 2011 and 2024, compared to 511 for Microsoft and 220 for Amazon. However, these figures are generally in line with each company’s broader investment numbers—AI firms make up between 25% and 30% percent of each company’s investment portfolio for the 2011-2014 period.

Figure 5: Big Three Investments into AI/ML Companies by Investment Count, 2011-2024

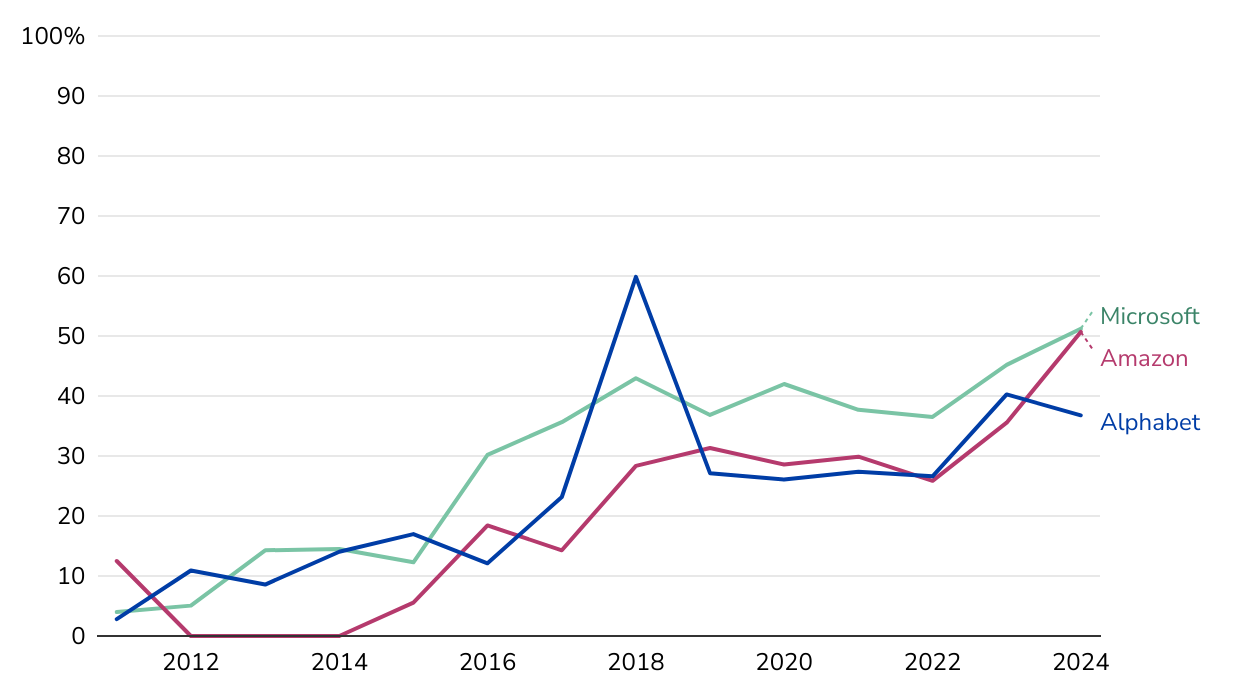

However, as shown in Figure 6, the share of investments targeting AI companies has been increasing over time for each of the Big Three. Since 2023, both Microsoft and Amazon have devoted half of their investments to AI companies.

Figure 6: Percent of Big Three Investments into AI/ML Companies, 2011-2024

The Big Three have considerable resources at their disposal that can be used to enmesh themselves into key companies and markets. These resources are dispersed through traditional financial means of mergers and acquisitions, venture capital, and seed money across the world. Additionally, their tailored accelerator programs provide not only cash and mentoring, but critical cloud computing credits that lure and lock compute-intensive companies into their cloud ecosystems.

Alphabet, Amazon, and Microsoft rank among the most valuable—and powerful—companies in the world, and as the leading global providers of cloud services, they play an outsized role in the development of digital technologies like artificial intelligence. Through corporate investments, as well as cloud infrastructure build-outs and open-source software development, these companies are expanding their global influence and their power to steer the growing digital economy.