In this next series of data snapshots, we revisit some of CSET’s past surveys and explore how their results reinforce our research findings and policy recommendations.

Using a 2019 CSET survey of PhD recipients from top U.S. programs for artificial intelligence (AI), we drew connections to more recent CSET research on the AI workforce. We identified respondents based on authorship of a dissertation for a PhD program listed in U.S. News & World Report’s 2018 ranked AI universities. Details about the survey and findings are reported in two 2020 CSET data briefs, “Career Preferences of AI Talent” and “Immigration Pathways and Plans of AI Talent.”

One question asked respondents to rank factors they saw as the most important resources for a country to build its AI talent pool; the result wasn’t reported in the two briefs because fewer people provided an answer. We found respondents were generally aligned on the factor they consider most important (a robust domestic university and research ecosystem), but there was some variation in subsequent rankings based on whether respondents worked in academia or the private sector. The factors respondents considered important for building a domestic AI talent pool closely aligned with CSET’s U.S. AI workforce policy recommendations.

The survey collected 254 responses from AI PhD recipients working in academia, the private sector, and the public sector who were identified based on their authorship of an AI/ML-relevant dissertation between 2014 and 2018 at a top-ranked U.S. university. It included a short battery of questions on AI talent development that were presented to half of the survey respondents, selected randomly. One question asked, “What are the most important resources for a country to build its AI talent pool? Rank 5 factors in order of importance.” The resources that respondents were asked to rank were:

- Strong domestic STEM education;

- Government funding for AI research and development;

- Strong university and research ecosystem;

- Strong private sector ecosystem; and

- Policies and culture friendly to foreign talent.

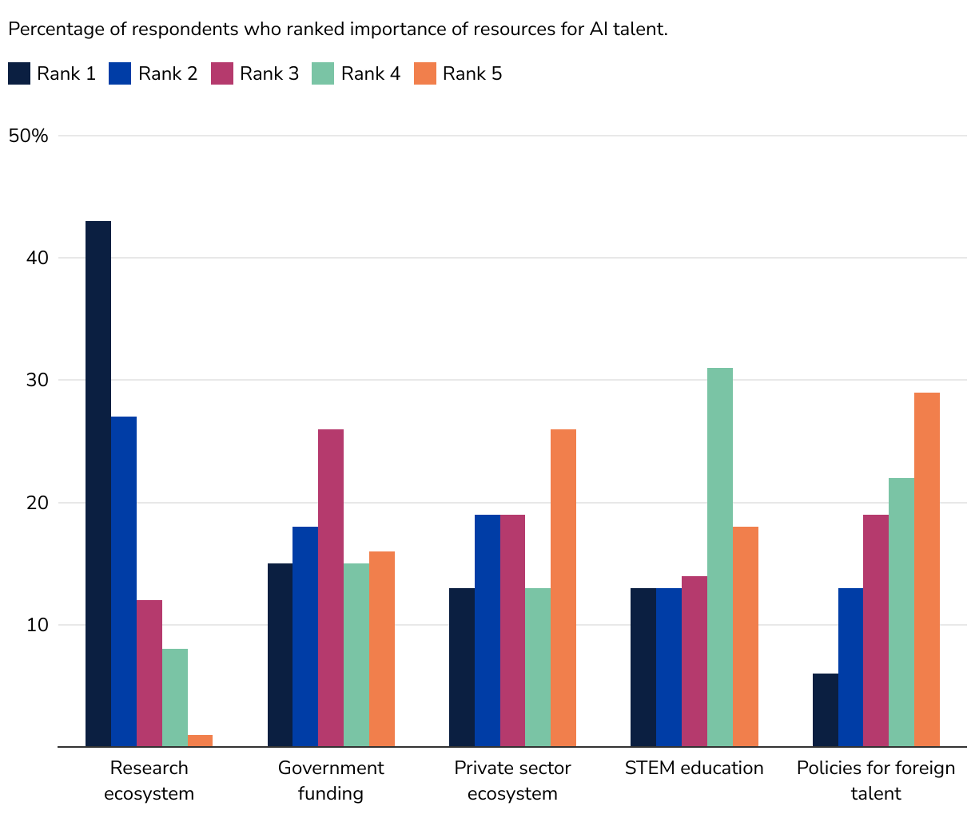

As seen in Figure 1, respondents considered a strong university and research ecosystem to be an important resource, with 77 percent ranking it first or second. Government funding for AI R&D was also considered critical; it was the most common resource ranked third. Strong domestic STEM education was most frequently ranked fourth, and policies and culture friendly to foreign talent was most frequently ranked last. A strong private sector ecosystem had the most variation in ranking, with about 20 percent ranking it second or third, and 30 percent ranking it last.

Figure 1. Respondent Ranking of Resources for Building Domestic AI Talent

Source: CSET Survey of U.S. AI PhDs.

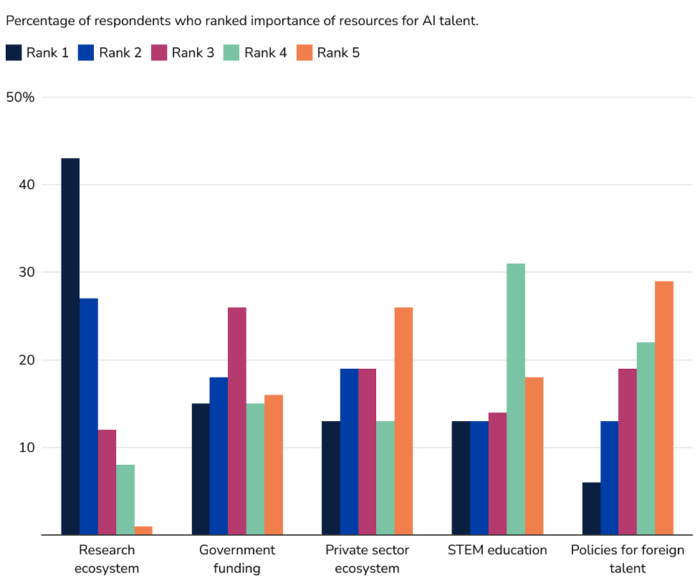

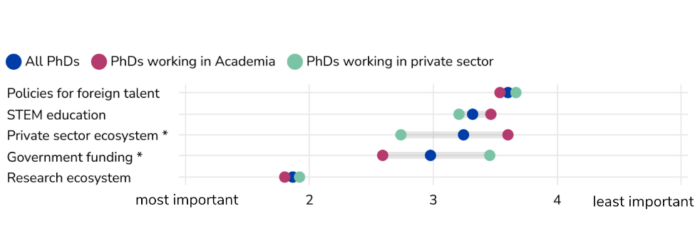

We can also examine responses to assess whether rankings differed based on respondents’ employment sector. Respondents working in academia ranked government funding for AI R&D higher than respondents working in the private sector. More than 75 percent of respondents in academia ranked it as a top three resource as compared to 50 percent of PhDs working in the private sector. Conversely, respondents in the private sector ranked a strong private sector ecosystem higher than PhDs in academia; 71 percent ranked it as a top three resource compared to 46 percent of those in academia. There is a statistically significant difference in mean ranking for these two factors, as seen in Figure 2, which compares the mean ranking for each factor between these two groups (with 1 representing most important and 5 representing least important).

Figure 2. Mean Ranking of Resources for Building Domestic AI Talent, by Employment Sector

Source: CSET Survey of U.S. AI PhDs.

Respondents were also given the opportunity to list other resources they consider to be critical to building a robust domestic AI talent pool. Some respondents specified forms of educational support to encourage basic knowledge of AI and creative thinking around AI development (e.g., “early education in computer literacy”). Others reinforced the importance of immigration to attract foreign talent (e.g., “visa sponsorship”). A few respondents noted the need for diversity in hiring and education to build a robust talent pool; this alternative to the pre-set list of factors was noteworthy because the list focused on resources such as funding and robust ecosystems.

A recent CSET report recommends ways to increase diversity in the AI workforce by providing alternative pathways, specifically through increased support for community colleges and technical colleges. While a four-year degree remains the primary method of entering into an AI career, expanding alternative pathways will diversify this talent stream and bring attention to the many necessary non-technical roles in the AI workforce. It is important to ensure that technical and community colleges are included in the conversation when considering investments in post-secondary AI education and scholarships. Understanding and promoting a whole-systems approach to sustaining and building the domestic environment is necessary for acknowledging and supporting the various entry points to an AI career.

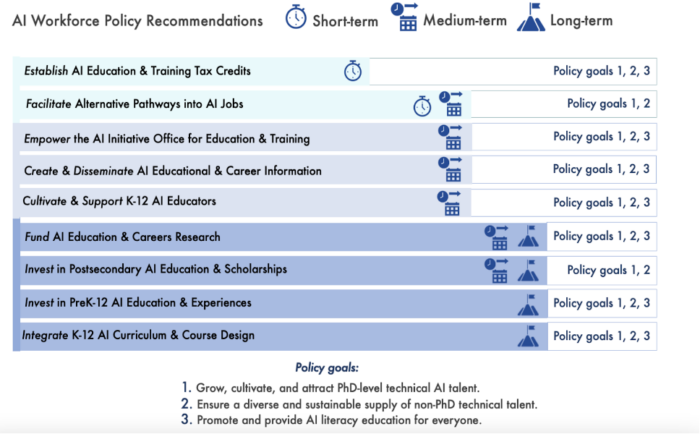

The resource rankings from our survey of top U.S. AI PhD recipients provides additional evidence supporting CSET’s AI workforce research and policy recommendations, as summarized in Figure 3.

Figure 3. Summary of CSET AI Workforce Policy Recommendations

Look out for our next Data Snapshot comparing findings from a 2019 CSET survey of AI professionals to a more recent survey of tech sector professionals fielded by the RAND Corporation.